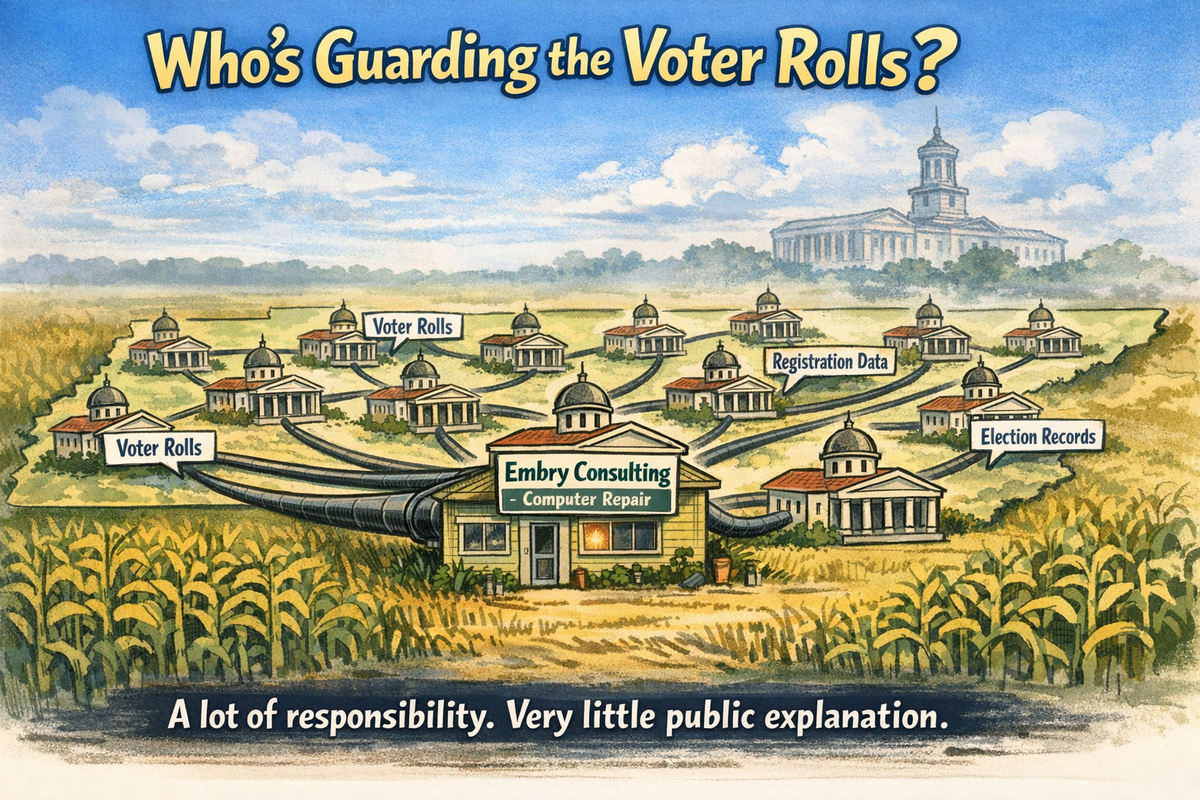

A small Tennessee firm quietly supports voter rolls in 91 counties raising questions about transparency, oversight and trust.

A TruthWire News Investigative Series

Series Introduction

Elections do not begin on Election Day.

Long before a ballot is cast or a vote is counted, elections are shaped by systems most voters never see: voter registration databases, administrative software, and the processes that determine who is eligible to vote, where they vote, and how their registration is verified.

In Tennessee, as in most states, voters are routinely told these systems are secure. Election officials emphasize integrity, reliability, transparency, and public trust. Yet in this situation, transparency is nowhere to be found. And when citizens ask basic questions about how voter registration systems are managed—who provides the software, how vendors are selected, what safeguards are in place, and what level of cybersecurity must be maintained—answers can be surprisingly difficult to obtain.

That opacity matters because voter rolls are not clerical spreadsheets—they are core election infrastructure. Without accurate rolls, turnout reports, precinct assignments, and provisional-ballot decisions cannot function reliably. Inaccurate or poorly protected voter rolls can also introduce administrative vulnerabilities, as cybersecurity researchers have illustrated in national case studies.

This series examines public records, state law, vendor documentation, minutes from meetings of public governmental entities, and unanswered questions surrounding the voter registration systems used by the vast majority of Tennessee counties. It does not allege wrongdoing. It does not claim elections were compromised. It asks whether transparency and documentation match the level of responsibility these systems carry.

At a time when confidence in elections is fragile, sunlight matters.

Editor’s Note / Methodology

This series is based on:

• Public records requests submitted to county election commissions and the Tennessee Secretary of State

• Review of Tennessee election statutes and State Election Commission records

• Vendor invoices and written correspondence

• Minutes from public governmental bodies

• Publicly available cybersecurity research and national case studies

This reporting does not allege illegal conduct or malicious intent by any individual, company, or public agency. Where documentation was requested and not produced, that absence is reported as such. References to cybersecurity risks are general and educational, based on expert research, and are not presented as evidence of compromise in Tennessee elections.

Most Tennesseans rarely think about voter rolls unless something goes wrong. They assume their registration is accurate, their eligibility is clear, and their county and the state have systems in place to manage those records responsibly. For the most part, election infrastructure operates quietly in the background, invisible to voters, and that is by design.

But sometimes, the absence of attention becomes the story.

In at least 91 of Tennessee’s 95 counties, voter registration databases and software used during early voting and on Election Day are supported by a single private vendor: Embry Consulting LLC. The remaining counties—Shelby (Memphis), Davidson (Nashville), Hamilton (Chattanooga), and Knox (Knoxville)—use other systems or processes.

Embry Consulting is based in Friendship, Tennessee, a rural town in Crockett County with a population of roughly 613 people. Crockett County itself has fewer than 14,000 residents. Geography alone does not determine technical capability, and small firms can and do provide specialized services effectively.

What makes Embry Consulting notable is not its location, but the scope of responsibility it appears to hold relative to the limited public information available about how it came to do so.

Invoices obtained through public records requests show that Embry Consulting provides support for voter registration software commonly referred to as “VoterCentral.” Counties typically pay between $5,000 and $6,500 per year for this service. With participation from at least 91 counties, the collective annual cost to taxpayers is approximately $460,000.

These systems do not count votes. But they manage the voter rolls—the databases that determine who is eligible to vote, where voters are assigned, and how registration status is verified at polling places. That role places the vendor at the center of one of the most sensitive administrative layers of election infrastructure.

Yet a review of Embry Consulting’s public-facing website, https://embrypc.com/, presents a very different picture. The site describes a general IT and computer repair business. It does not publicly describe voter roll software management as a specialized service. It does not outline election-system expertise. It does not list cybersecurity certifications or credentials commonly associated with managing sensitive government databases.

This absence does not mean such expertise does not exist. It does mean that voters cannot independently verify it.

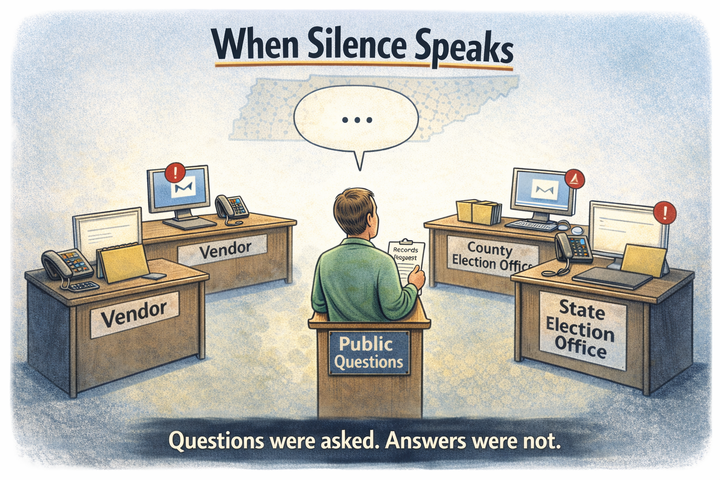

As questions emerged about how a single vendor came to support voter registration systems across nearly the entire state, citizens began asking election officials and the vendor routine, governance-focused questions. They were not accusatory. They were foundational:

• Who selected the vendor?

• What qualifications were evaluated?

• What was the process to deem Embry the best option?

• What made Embry stand out?

• What security standards apply?

• How is oversight conducted?

The answers proved difficult to obtain.

The vendor declined to engage directly. County officials produced invoices but little context. State and county officials confirmed they had no contract with the vendor. Inquiries were redirected or went unanswered.

As a result, voters are left with an unusual situation: a firm few Tennesseans have heard of plays a central role in election administration, yet the process by which it obtained and maintains that role remains largely opaque. And that opacity casts doubt on the entire election process.

Trust in elections depends not only on outcomes, but on understanding how systems are managed, how vendors are selected, and the level of security needed to protect the process. When foundational components of election administration operate without public explanation, questions are inevitable—not because of suspicion, but because transparency has not been provided.

This series begins not with an allegation, but with a simple observation: voter registration systems carry enormous responsibility, and the public deserves to understand how that responsibility is overseen.

In Part 2, we follow the money. Counties across Tennessee collectively pay hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars each year for voter registration software support—but public records reveal something unusual. Despite the scale and sensitivity of the service, at least one county acknowledges it has no written contract governing the work.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()