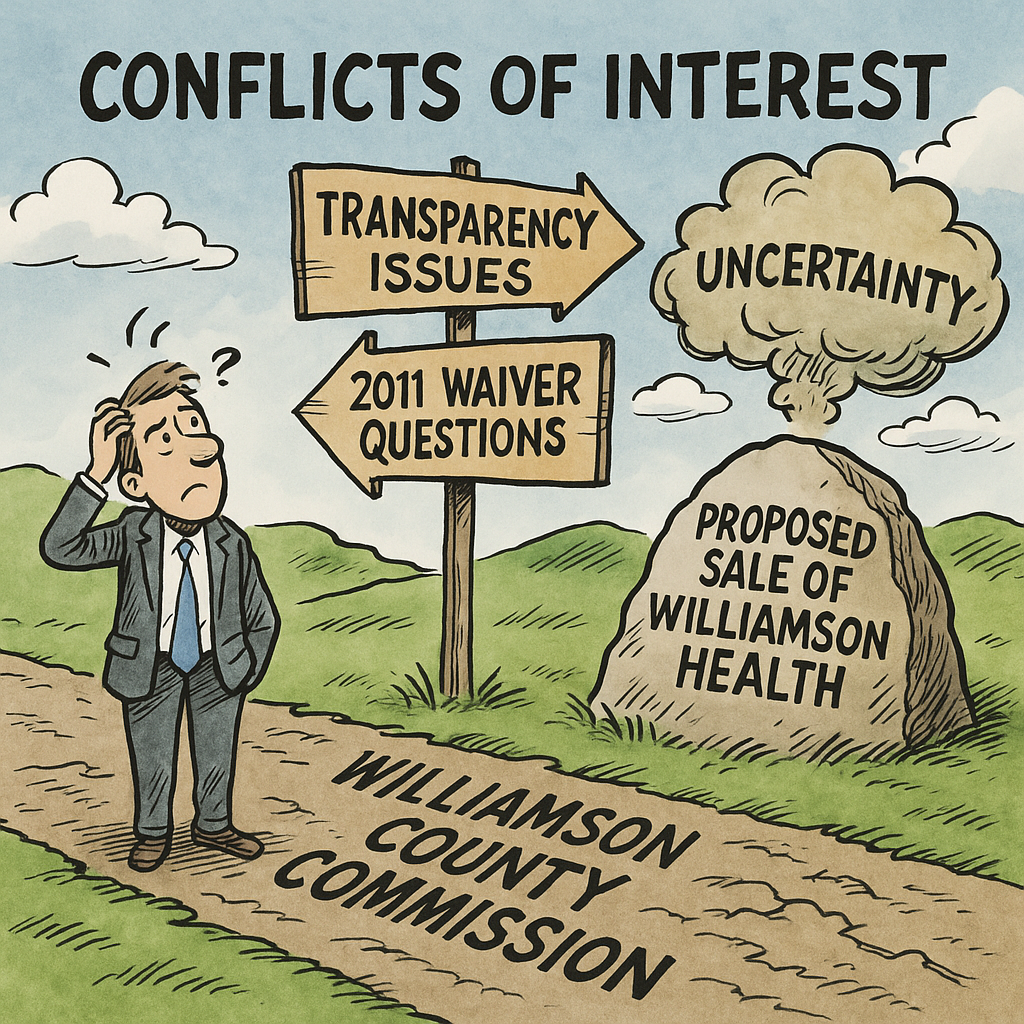

Williamson County’s handling of the possible hospital sale has ignited concerns over transparency, legal authority, and conflicts of interest. Old waivers, limited counsel options, and dual representation have left many questioning who is truly protecting taxpayers.

By Kelly Jackson | TruthWire News | November 19, 2025

Last week’s Williamson County Commission meeting revealed escalating tension and uncertainty surrounding the proposed sale of Williamson Health. What began as a procedural vote to approve an hourly rate for outside legal counsel quickly expanded into a debate over transparency, legal authority, and potential conflicts of interest — leaving commissioners and residents with more questions than answers.

The evening’s first significant moment came when the Commission was asked to approve a $900 hourly rate for mergers-and-acquisitions attorney Jesse Neal. Commissioners were told they were not selecting Neal, only approving compensation, because state law — according to County Attorney Jeff Mosley — gives the mayor exclusive authority to hire outside counsel while the Commission’s role is limited to approving payment. No resolution was presented, and no candidates were vetted. Yet by approving the rate, the Commission effectively finalized the mayor’s choice and surrendered any remaining ability to secure independent counsel of its own. The vote came with little space for delay, creating a sense that commissioners were being pushed into ratifying a decision made long before they were invited into the process. Commissioner Chris Richards cast the lone “no” vote.

Commissioners also learned during the meeting that Mosley and Mayor Anderson had begun contacting potential outside attorneys months earlier. Because any lawyer previously contacted becomes conflicted out under ethics rules, the delay in informing the Commission meant that by the time the issue reached the floor, the pool of eligible attorneys had been dramatically narrowed. In practice, this left the Commission with no meaningful alternatives and allowed the Mayor and Mosley to determine who the outside counsel would be.

The conflict-of-interest concerns intensified when Richards disclosed that he had filed a professional-conduct complaint against Mosley, alleging a violation of Rule 1.7 for simultaneous representation of both the County Commission and the hospital board. Mosley responded by emphasizing that both entities had signed conflict waivers, which permit dual representation unless and until the Board of Professional Responsibility rules otherwise. From the perspective of attorneys — including several commissioners with legal backgrounds — a waived conflict is not treated as a per se violation.

Beyond the broader legal debate, lingering questions surrounding a 2011 agreement have further complicated the conflict-of-interest issue. Mosley has referenced that decade-old document as evidence that a previous County Commission consented to a dual-representation arrangement. But whether such a consent remains valid more than a decade later is a matter of genuine dispute. The Commission that allegedly approved the waiver in 2011 is not the Commission that sits today, and the circumstances surrounding Williamson Health have changed dramatically since then. Legislative bodies cannot typically bind future versions of themselves to perpetual conflict waivers — particularly when the underlying facts have shifted so substantially. Even if a waiver existed in 2011, the question remains: can it reasonably be considered informed consent for the situation now unfolding?

For that reason, several attorney-commissioners — including Brian Clifford and Sean Aiello — reacted strongly to Richards’ public framing of the conflict as an established fact. The sharpness of their response reflected not only the legal posture but also existing political dynamics, as both have clashed with Richards in prior debates and suggested the complaint stemmed from personal disagreements rather than governance concerns. In a public meeting, such characterizations can influence how seriously the public perceives the complaint.

However, many residents and non-attorney commissioners saw the issue far more plainly. To them, one attorney representing both the Commission and the hospital board — while the county explores the possible sale of a major public asset — appears inherently conflicting regardless of waivers. Even the decision to bring in separate mergers-and-acquisitions counsel reinforced the perception that unified representation may not be appropriate for every element of the process.

A related legal disagreement emerged over whether the Commission has authority to hire its own independent counsel. Richards pointed to a Tennessee Attorney General opinion acknowledging that certain local bodies may retain separate counsel when their interests diverge from those of executive officials. Mosley countered that the opinion applies only to the specific boards named in that request and does not extend to county commissions. To rely solely on the fact that county commissions aren’t explicitly listed in the opinion — rather than considering its broader intent to cover similarly situated bodies — reduces the argument to a procedural loophole.

Later in the meeting, Commissioner Greg Lawrence introduced a proposal asking the General Assembly to enact a Private Act or amend state law so that, should the hospital ever be sold, the proceeds would return to the County Commission rather than a private foundation with an unelected board. The measure passed 17–6.

As debate continued, Commissioner Mary Smith moved to defer Richards’ resolution on independent counsel until January. Once the Commission approved Neal’s rate — and with it, the structural arrangement preferred by Mosley and Mayor Anderson — the purpose of Richards’ resolution had been overtaken. Richards withdrew it, acknowledging that any future version would need to reflect the significantly altered circumstances.

By the end of the night, the Commission had approved the rate of an attorney it did not select, discovered that its range of potential alternatives had been narrowed months earlier, deferred its own oversight efforts, and left unresolved the broader conflict-of-interest issues raised during the meeting. County officials maintain that no final decision on a sale has been made and that any eventual transaction would require multiple layers of approval. Still, the combination of an active RFP, high-priced outside counsel, a dual-representation structure, unresolved questions surrounding a 2011 waiver that may or may not still have legal relevance, and the disappearance of independent counsel options has intensified public concern.

Richards was trying to reassert the Commission’s independence at a moment when its influence over a major public decision is narrowing. That push has been put on hold. And as every level of government demonstrates, once a governing body hands off its power, getting it back is far harder than giving it away.

If you support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()