The promise of “lifting up” through low-income housing sounds noble. But history asks: do these projects elevate struggling families—or slowly pull entire neighborhoods down with them?

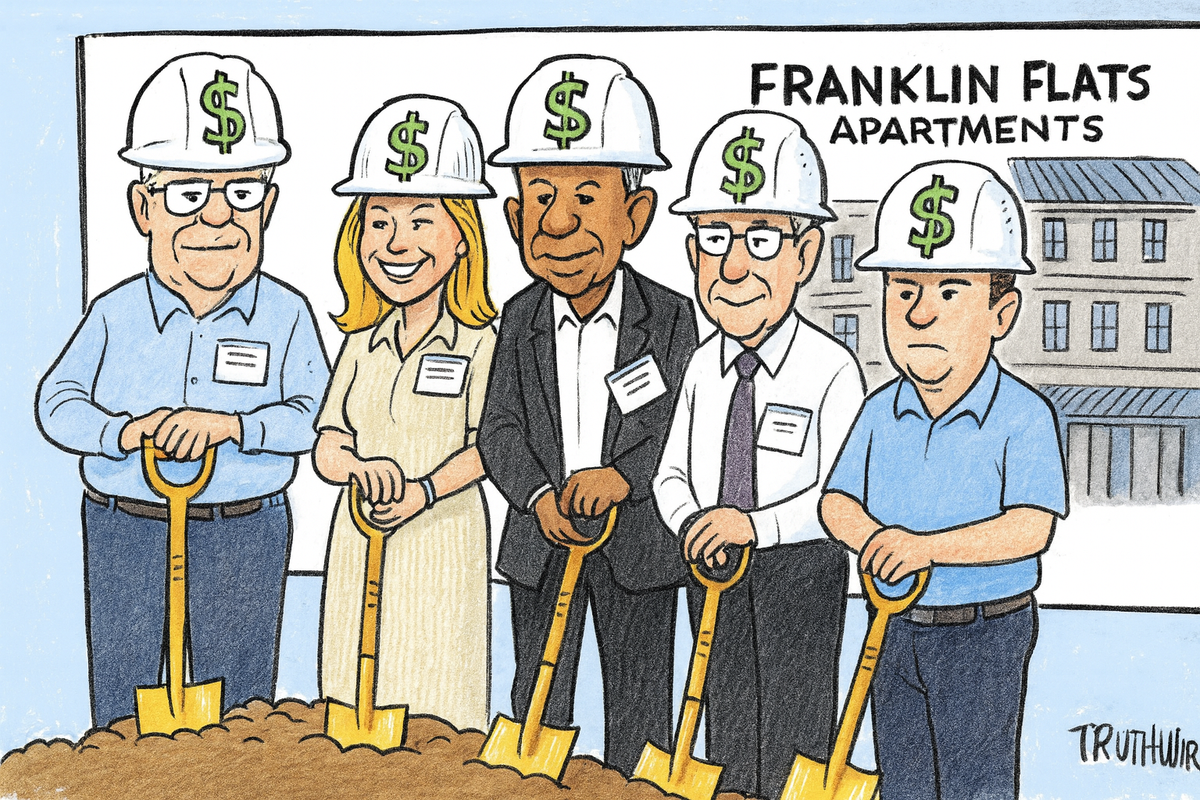

Franklin Flats is scheduled to open in 2026 as an income-restricted housing project. On paper, the idea is simple and appealing: place deeply discounted units in a high-opportunity city and let families benefit from safer streets, better schools, and closer jobs. That’s the promise. The question for Franklin residents—regardless of party—is what such projects have historically delivered once the ribbon is cut, and how those outcomes affect the people who already live nearby.

Decades of research tell a consistent story about large, single-site subsidized housing. The problems are not inevitable, and they are not about the worth of the people who move in. They are about structure. When a city concentrates lower-income households in one location, three pressures tend to show up unless the city is unusually disciplined about management and support.

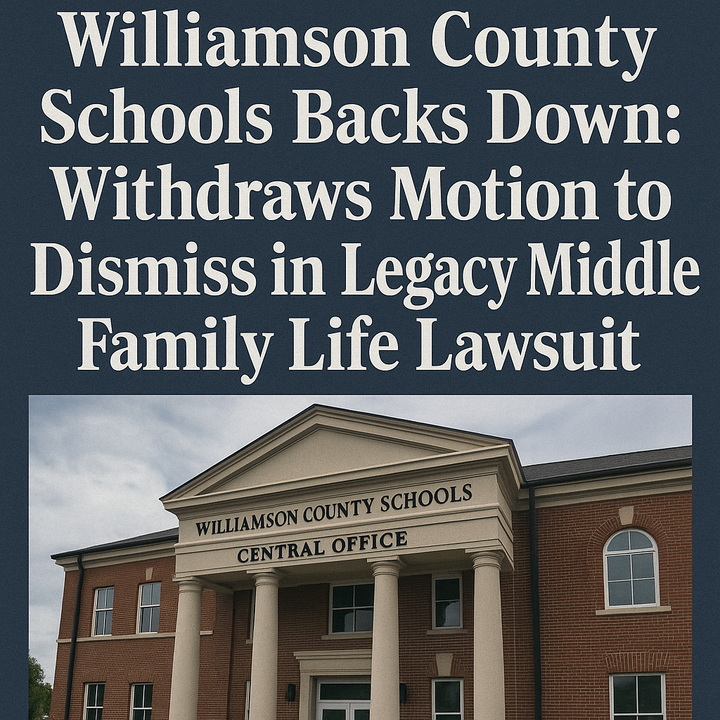

First, schools. Classrooms that suddenly absorb higher mobility, more remediation, and more trauma need more adults and more time. If resources don’t arrive at the same pace as new needs, test scores dip, behavior issues rise, and teachers burn out. None of this is a moral judgment; it’s math. Williamson County already allocates roughly 70 percent of its nearly one-billion-dollar annual budget to education, yet the district still struggles to meet the needs of its existing, largely high-income student base. Introducing an influx of higher-need students without targeted support doesn’t just stretch teachers thinner—it changes the balance of attention and resources for every classroom. A higher-need student body requires smaller groups, tutoring slots, counselors, and consistent attendance enforcement. If those pieces lag, families who bought into a school zone for its reputation discover the bargain has changed.

Second, crime and disorder. “Crime” often begins as nuisance: poorly managed parking, noise that runs late, litter, vandalism that doesn’t get fixed, common areas that feel unclaimed. Those signals erode the informal social control that makes good neighborhoods work. Residents call less because it feels pointless. Patrols show up more because calls are up. Property managers patch instead of repair. Eventually the same block that felt stable and neighborly feels fragile. Again, this is structural. High-turnover rentals, thin maintenance budgets, and vague house rules create conditions where a few bad actors define the tone for everyone.

Third, upkeep. Franklin’s reputation rests on something simple: people take care of what’s theirs. If a project opens with inadequate reserves, weak enforcement, or a management company that isn’t empowered to hold the line, the buildings age fast. Hallways get dingy. Landscaping goes first. Trash enclosures overflow. Once the “look” slides, nearby property owners shoulder the bill—first in HOA costs to buffer the decline, then in valuation.

These patterns aren’t speculative—they’re historical fact. Studies from the Urban Institute and Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies have documented how concentrated public housing consistently struggled with maintenance, safety, and school outcomes. The story of St. Louis’s Pruitt-Igoe project remains the most famous example—a case where good intentions collided with poor structure, political neglect, and social isolation. Modern research, including the Brookings Institution’s mixed-income housing analysis, shows that outcomes improve dramatically when affordability is dispersed rather than concentrated.

Franklin sits in the heart of Williamson County—an area marked by both prosperity and a strong tradition of evangelical faith. Most here genuinely believe in the biblical call to love their neighbors and to help those who lack. Acts of service, generosity, and community outreach are woven into the culture; charitable giving and mission work are not political gestures but expressions of faith. Yet Scripture also offers another side of that command: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” In other words, reciprocity is biblical. Loving others doesn’t mean surrendering prudence or abandoning standards.

There’s a difference between charity and subsidy, just as there’s a difference between opportunity and outcome. Opportunity gives people the tools to rise; outcome demands that everyone end up in the same place regardless of effort or discipline. The first strengthens a community; the second weakens it. When cities like Franklin endorse housing projects under the banner of “equity,” they are often endorsing a system that ignores the role of personal responsibility—the daily choices that sustain order, safety, and pride of ownership.

Extending help to those in need doesn’t require importing every social challenge into our own backyards, especially when history shows that doing so often brings decline, disorder, and strain on local systems already stretched thin. True stewardship—biblical stewardship—means caring for what God has entrusted to us: our homes, our neighborhoods, our schools, and our safety. Franklin’s residents can be both generous and discerning, charitable without being naïve.

The difficulty with projects like Franklin Flats is that they are often supported most strongly by the city’s more progressive residents, who equate acceptance with virtue and standards with judgment. But moral worth isn’t measured by how loudly one proclaims tolerance; it’s reflected in the long-term fruits of those decisions. When “compassion” becomes permission for chaos, or when the refusal to hold others accountable is mistaken for grace, everyone pays the price—including the very people such projects claim to help.

People move to Williamson County—and to Franklin in particular—because it strikes a rare balance: strong schools, safe neighborhoods, and relatively low property taxes. That’s the draw. But that stability has not been preserved by restraint; it’s survived in spite of leadership that talks like fiscal conservatives while governing like growth lobbyists. Development has been fast, dense, and often approved without corresponding infrastructure or budget offsets. And when the inevitable costs follow—new roads, more classrooms, expanded police and fire coverage—the solution from city and county officials is almost always the same: raise taxes rather than rein in spending or slow approvals.

That pattern has put Franklin on a slow but certain trajectory toward the same overbuilt, overtaxed spiral seen in cities that once shared its promise. Each time another large-scale subsidized housing project is approved, the long-term math worsens. More residents mean more strain on schools, more wear on roads, and more public expense. The result isn’t shared prosperity—it’s higher bills for the very homeowners who worked hardest to create and sustain Franklin’s quality of life.

While supporters of projects like Franklin Flats often speak in terms of compassion, the financial reality tells another story. The cost of accommodating new infrastructure and public services doesn’t vanish—it’s redistributed. Homeowners end up paying more, receiving less, and watching the standard of their city erode under the weight of decisions made in the name of “equity.” This isn’t an argument against helping those in need; it’s an argument for honesty about who truly pays and who truly changes.

If Franklin Flats is being sold as a test of compassion, the reality is far more transactional. It’s the first in what could become a long line of taxpayer-funded ventures justified by virtue and driven by revenue. The least the city can do is meet the standards it preaches.

It’s also worth acknowledging the timing: the Board of Mayor and Aldermen advanced approvals related to Franklin Flats during the same election cycle that saw development-aligned donations show up across city races. In small campaigns, $1,000–$1,900 checks matter. That doesn’t prove a cause-and-effect relationship; it does explain why residents expect more documentation and firmer conditions when votes align with donor interests. With only Matt Brown and Patrick Baggett facing serious challenges this year, scrutiny is not cynicism—it’s accountability.

Franklin can be generous and careful at the same time. We can welcome families who need price relief without pretending history doesn’t exist or that human behavior will magically change when accountability is removed. If Franklin Flats is going to be our city’s test of honesty, it should begin with the city itself.

Franklin’s BOMA elections are at the end of this month, and the County Commission and County Mayoral races follow next year. Choose wisely.

If you support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

COME TO OUR EVENT FOR A GREAT EVENING OF BBQ AND GRASSROOTS PATRIOTISM!! SCAN THE QR CODE, OR CLICK HERE!!

Comments ()