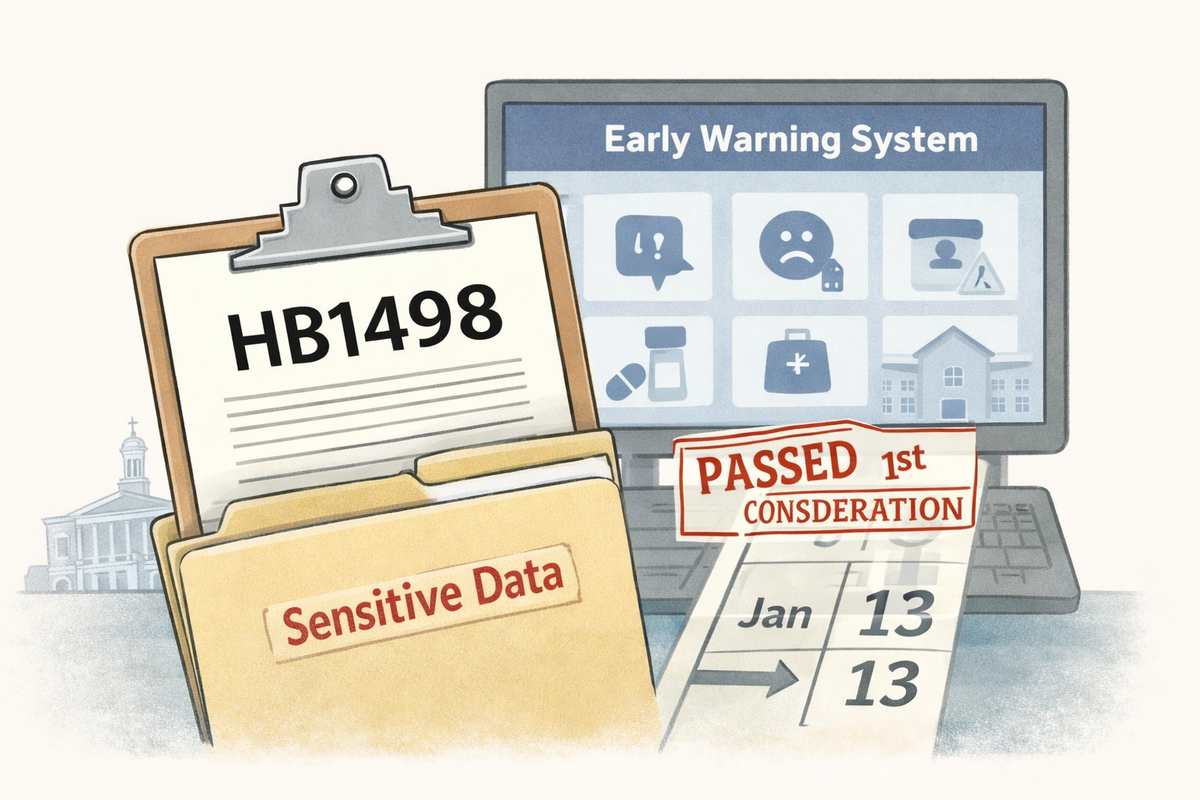

TN’s new session opens with HB1498: a student “early warning” tracking mandate—plus a timeline glitch that raises privacy and process concerns.

Today, January 13, marks the first day of Tennessee’s new legislative session—and if the early signals are any indication, the public is being asked to play catch-up from day one. A newly filed proposal, HB1498 by Rep. Jay Reedy (with a Senate companion SB1487 by Sen. Powers) would create a statewide framework for tracking and reporting students’ “early warning signs,” including mental-health indicators and behavioral concerns, through a mandated computer-based system.

But what has drawn immediate attention is something even more basic: the public record. A screenshot captured January 12, 2026 appears to show the Senate companion already labeled “Introduced, Passed on First Consideration” dated January 13, 2026—a date that had not yet occurred at the time of the screenshot. Maybe it’s a harmless website artifact. Maybe it reflects internal scheduling that posted early. Either way, it’s not a confidence-inspiring start for a session that should be prioritizing transparency—especially when the bill in question deals with children, sensitive data, and a reporting pipeline that could follow students for years.

If this is how the session opens—major policy with significant privacy implications paired with a public-facing timeline that appears to run ahead of reality—things so far aren’t looking great.

What HB1498 would do

HB1498 creates a new section of Tennessee law called the “Early Behavioral Intervention and Reporting Act.” It defines “early warning signs” as evidence of safety, health, or behavioral issues a student exhibits. The definition is broad and includes but is not limited to: signs a student is engaging in or being victimized by harassment, intimidation, bullying, or cyberbullying; making or receiving threats of violence; and exhibiting signs of substance abuse, mental health issues, self-harm, or suicidal ideation.

The bill requires each Local Education Agency (LEA) and public charter school to implement a computer-based system that teachers and staff must use to input data about early warning signs. Districts must ensure training to identify warning signs and to enter data into the system.

The system must: (1) align with existing harassment/bullying policies, the School Discipline Act, and school safety plans; (2) include a database capable of receiving and maintaining student data; and (3) immediately notify the LEA’s threat assessment team (or a designated charter employee) when a warning sign is entered.

Once notified, designated personnel must review the entry and prior entries for that student and decide whether further action is needed.

The bill also mandates annual reporting to the Tennessee Department of Education. The report includes totals and disaggregated counts of warning signs entered (by teachers and staff, with further breakdowns), the number of students who had multiple warning signs entered, general descriptions of warning sign types, and general descriptions of actions taken. It explicitly prohibits including details that would allow a student to be identified and requires compliance with FERPA and other privacy laws. Enforcement is real: if the commissioner of education finds noncompliance, the commissioner may withhold state funds until the LEA or charter school complies. The bill takes effect July 1, 2026, with an exception for districts that already had a system in place before that date and continue to use it.

Privacy concerns: sensitive information at scale

The central issue is that HB1498 would normalize the collection of highly sensitive information about minors—especially mental health indicators, self-harm, and suicidal ideation—into a formal, computer-based reporting system that triggers immediate internal escalation. Even if the annual state report is de-identified, the underlying district database still exists, and it will contain information that could shape how adults view a child for years.

The bill does not answer basic questions that matter in the real world:

- Who has access to the database and individual entries beyond the threat assessment team?

- How long is data retained—months, years, or indefinitely?

- Can parents or students challenge inaccurate entries or correct the record?

- What security standards apply if districts use vendors or third-party platforms?

- How is misuse prevented, such as using behavioral flags for unrelated purposes?

Saying “comply with FERPA” is not the same as building adequate guardrails. FERPA primarily regulates disclosure of education records; it does not automatically solve risks created by mass collection, broad internal access, or long-term retention of subjective behavioral notes. A statewide mandate that pushes districts toward a centralized behavioral tracking system should include clear limits and protections—especially when the categories include mental health and suicidal ideation.

Constitutional friction: speech, due process, and equal protection

HB1498 is not a criminal law, but it can still create constitutional problems through implementation.

Speech: “Threats” are included in the warning-sign definition, but the line between a true threat and protected expression is not always clear in school settings, especially when social media and secondhand reports are involved. A system that encourages staff to document and escalate student speech—without clear standards—can chill protected expression and invite over-reporting.

Due process: The bill creates a pathway where staff input triggers immediate notification to a threat assessment team and potential “further action.” If that action results in discipline, exclusion, referrals, or restrictions, a student may effectively suffer consequences based on an internal record they may never see. Without defined standards for notice, review, and correction, the system risks becoming a mechanism for accumulating allegations that influence outcomes without meaningful procedural safeguards.

Equal protection and bias: Broad, subjective categories invite inconsistent application. Students with disabilities, neurodivergent students, and students in certain demographic groups can be disproportionately flagged based on interpretation rather than objective risk. Even if disparities do not prove a constitutional violation by themselves, they are a predictable result of vague categories combined with mandated reporting—and they will matter if this system becomes tied to discipline, placements, or law enforcement involvement.

The process concern: why does the timeline look wrong?

Even if one supports early intervention in principle, the rollout and transparency matter. The January 12 screenshot showing an action dated January 13 creates the appearance that the public tracking page can display steps as completed before they occur—or at least in a way a reasonable person could interpret that way.

There may be benign explanations: legislative websites sometimes preload calendar actions, “first consideration” is procedural rather than substantive, and posting could be tied to internal docketing. But the optics are not trivial. On the first day of session, with a bill that touches sensitive student data, the public should not be squinting at the website trying to figure out whether the process is moving normally.

If HB1498 advances, Tennesseans should demand clear answers:

- What committees will hear this bill, and when?

- What platform or software model is anticipated, and who provides it?

- What data retention, access, audit, and correction rules will apply?

- What parental notice, consent, or review rights exist, if any?

Bottom line

HB1498 is framed as early intervention and safety, but it mandates a statewide architecture for collecting and escalating student behavioral and health indicators—some of the most sensitive information schools can handle. The bill’s general privacy language does not substitute for clear, enforceable safeguards around access, retention, correction, and security. And when the public-facing bill history appears inconsistent—especially on the first day of session—lawmakers should expect skepticism.

Tennessee can pursue school safety without building a permanent behavioral dossier system on children. But if the legislature intends to do this, it should do so slowly, transparently, and with strict limits. If this is how the session begins, the early signs are not reassuring.

Should you have any concern about the bills passing through our legislative process, see the link here and find your legislators contact information. Then, make your voice heard!

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()