Counties pay nearly $500K yearly for voter-roll software, yet at least one reports no written contract defining the work.

In government, written contracts are not a bureaucratic nicety. They are the mechanism by which public accountability is made visible. Contracts define what a vendor is expected to do, what standards must be met, how performance is evaluated, and what happens if something goes wrong. They protect taxpayers, public officials, and the integrity of the systems being supported.

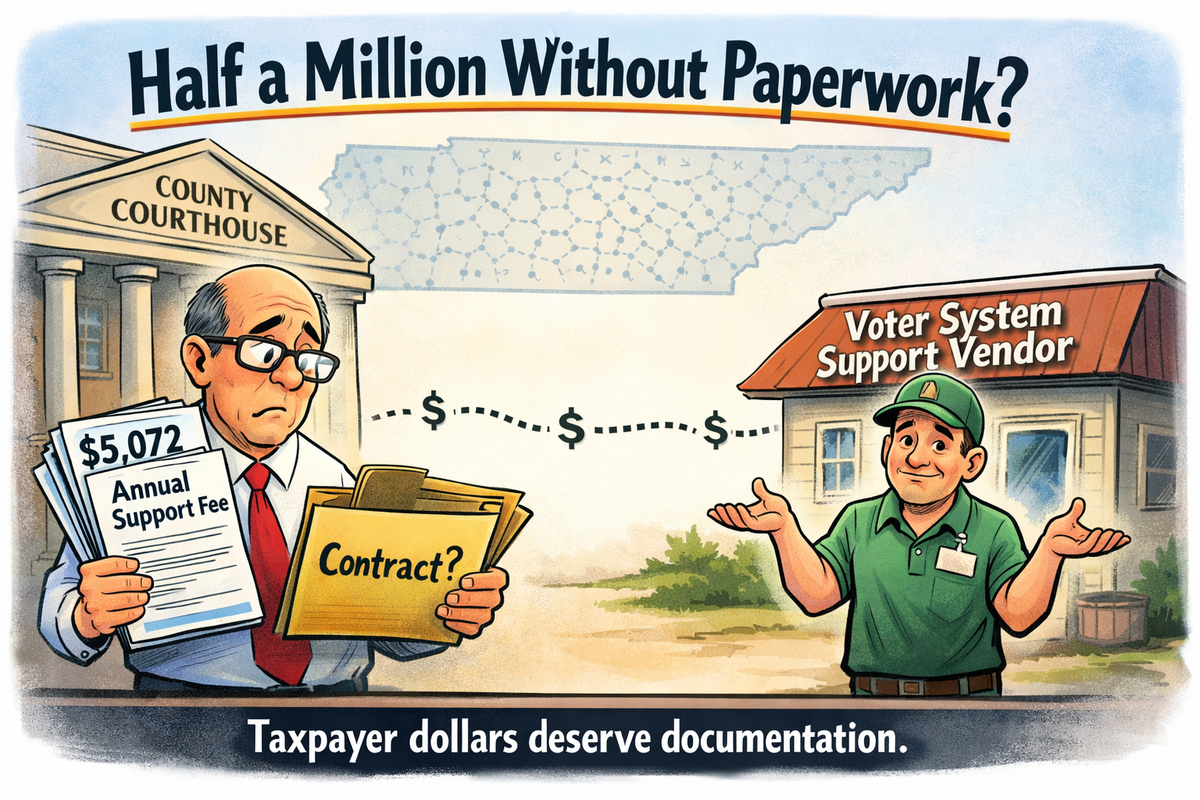

That is why one of the most consequential findings in this investigation is also one of the most straightforward: counties across Tennessee are paying a private vendor to support voter registration systems, yet at least one county acknowledges it has no written contract governing that work—and the state itself reports having none.

This conclusion comes not from inference, but from public records responses.

When a public records request was submitted to the Williamson County Election Commission, county officials provided invoices showing annual payments to Embry Consulting LLC for “VoterCentral Support.” Those invoices confirm that Williamson County paid Embry Consulting approximately $5,072 per year in both 2024 and 2025. But when asked for the underlying contract defining those services, the county’s election administrator stated plainly that Williamson County does not have a contract with Embry Consulting.

A similar request was submitted to the Tennessee Secretary of State’s Office, which oversees elections statewide. The response confirmed that the state has no records of a contract or invoices related to Embry Consulting. In other words, the state does not appear to be the contracting authority for this service, even though the software is used in the overwhelming majority of counties.

None of this establishes wrongdoing. Long-standing arrangements can persist for years, particularly when systems were adopted long ago and simply renewed annually. But the absence of written agreements raises an unavoidable governance question: how is oversight exercised when expectations are not documented?

The invoices themselves offer little clarity. They list an annual fee and a brief description—“VoterCentral Support”—but do not itemize what that support includes. There is no mention of system maintenance, security updates, monitoring, audits, reporting, or incident response. There is no service-level agreement specifying uptime, data integrity checks, or compliance requirements.

Without a contract, there is no public record defining:

- the scope of work

- cybersecurity or data protection standards

- performance benchmarks

- reporting obligations

- liability in the event of error or data loss

In most sectors that manage sensitive personal information—healthcare, finance, insurance—vendors are required to document compliance with security frameworks and submit to periodic review. These requirements exist not because vendors are suspected of wrongdoing, but because documentation is how trust is maintained.

Election systems, which underpin democratic participation itself, would reasonably be expected to meet a similar standard.

Instead, based on records reviewed for this investigation, nearly half a million dollars per year flows through county budgets collectively with no publicly available agreement explaining what taxpayers are paying for or how performance is evaluated.

It is important to be precise here. This reporting does not claim that Embry Consulting fails to perform its duties. It does not claim that counties are dissatisfied with the service. It documents that the public cannot verify how those duties are defined.

That distinction matters.

In the absence of a contract, oversight may still exist informally—through relationships, institutional knowledge, or historical practice. But informal oversight is difficult to examine, difficult to audit, and difficult to explain to the public when questions arise.

The lack of documentation also complicates another basic issue: consistency. With at least 91 counties using the same vendor, are all counties receiving the same services? Are security practices uniform? Are updates deployed simultaneously? Are issues tracked centrally or county by county?

Those are reasonable questions for any statewide system, yet without written agreements, there is no shared reference point for answers.

The situation also raises a broader policy question about procurement. Vendors supporting mission-critical government systems are typically selected through some form of competitive process, whether formal or informal. That process establishes why one vendor was chosen over others and what qualifications were considered.

In this case, public records reviewed do not include documentation showing how Embry Consulting was initially selected, whether alternatives were considered, or whether the arrangement has been re-evaluated as technology and cybersecurity standards have evolved.

Again, the absence of documentation does not prove that such a process never occurred. It shows only that it is not visible to the public today.

Election officials often emphasize that public confidence depends on trust. But trust is strengthened when systems are documented, standards are clear, and oversight is demonstrable.

Without contracts, voters are left with assurances but little evidence. That gap is not created by suspicion; it is created by silence.

As President Reagan famously articulated, "Trust- but verify". The question raised by this investigation is not whether counties should trust their vendors. It is whether voters are given enough information to trust the system themselves.

Coming Next in the Series

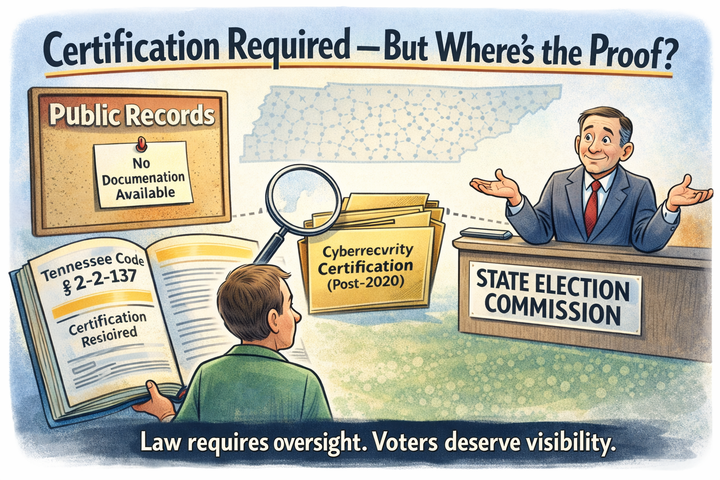

In Part 3, we turn to state law. Tennessee statutes require voter registration systems to be examined and certified, including consideration of cybersecurity practices. What does the law actually require—and what do public records show about how those requirements are implemented today?

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()