HB1491 reexamines how Supreme Court rulings reshaped religion in public schools and asks whether Warren Court doctrine went beyond the Constitution.

For more than half a century, religion in America’s public schools has been shaped less by legislatures and local communities than by a series of Supreme Court decisions issued during the era of the Warren Court. Those rulings transformed public education nationwide, removing organized prayer and Bible reading from classrooms and embedding what is now commonly described as the doctrine of “separation of church and state” into everyday school policy.

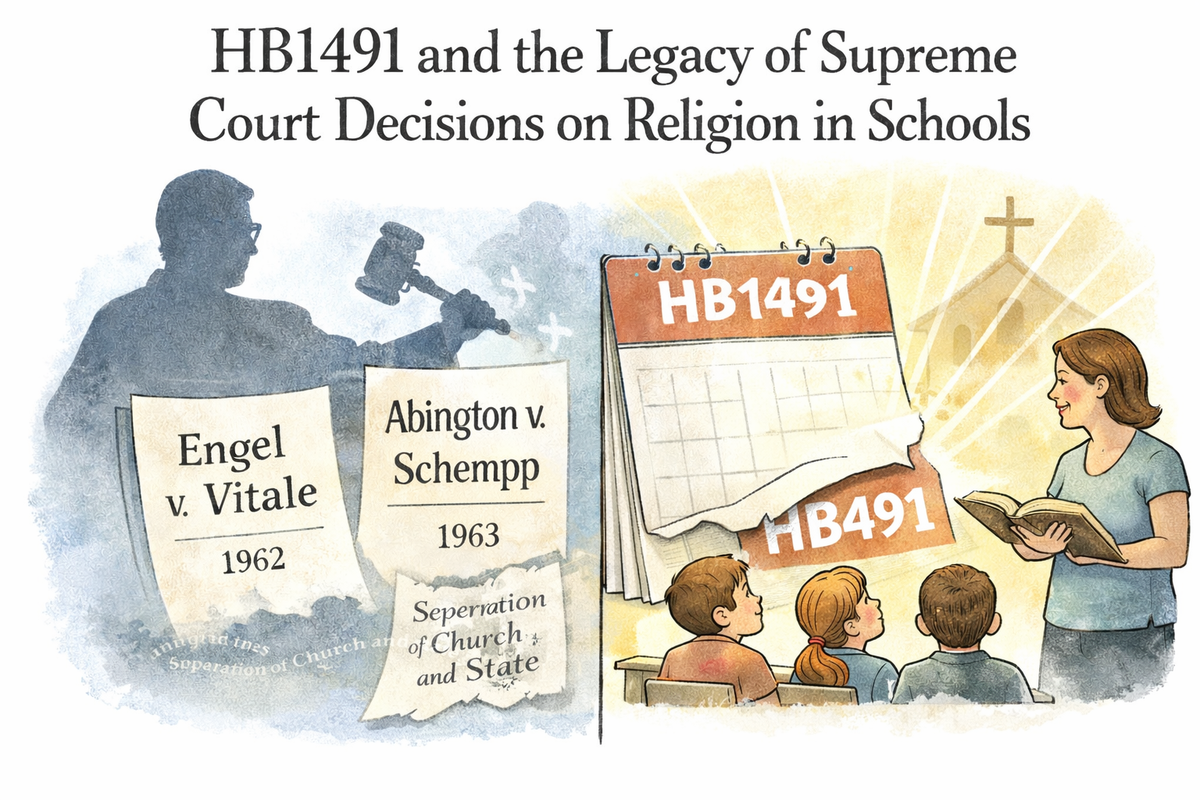

In Tennessee, lawmakers are revisiting that settlement. House Bill 1491, carried in the House by Gino Bulso of Brentwood and in the Senate by Joey Hensley, represents a direct challenge to the assumptions and enforcement practices that emerged from the Warren Court era. The legislation is not merely symbolic; it is an effort to rethink how constitutional doctrine has been applied in public schools for decades and whether that application has drifted beyond the Constitution’s original text and purpose.

The legal foundation for this debate begins with the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, which states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” By its plain language, the clause restricts Congress, not the states, and was originally understood to prohibit the creation of a national church or laws compelling religious belief or worship. For much of American history, states retained broad authority over religious expression in public life, including education. Bible reading, prayer, and moral instruction were common features of public schools well into the twentieth century.

That understanding changed in the mid-1900s when the Supreme Court began applying the Establishment Clause to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. During the Warren Court era, the Court adopted an increasingly expansive interpretation of what constitutes an “establishment” of religion. Rather than focusing solely on compulsion or the creation of an official church, the Court began examining whether government action could be perceived as endorsing religion or placing indirect pressure on individuals to participate.

The turning point came under Chief Justice Earl Warren. In Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court struck down a state-composed, non-denominational prayer recited in New York public schools. Although participation was technically voluntary, the Court held that government involvement in drafting and promoting prayer violated the Establishment Clause. One year later, in Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), the Court extended that reasoning to invalidate school-sponsored Bible reading and recitation of the Lord’s Prayer.

That case was consolidated with Murray v. Curlett, brought by Madalyn Murray O'Hair, one of the most prominent atheist activists of the era. O’Hair argued that any structured religious exercise within public schools was inherently coercive, regardless of opt-out provisions. The Court accepted that argument, concluding that the classroom environment itself exerted pressure on students, making even voluntary religious participation constitutionally suspect.

Those decisions did more than prohibit specific practices. In the decades that followed, school districts adopted an increasingly cautious posture toward religion altogether. Administrators and legal counsel treated Warren Court rulings not as narrow prohibitions, but as broad warnings. Bible instruction disappeared from curricula. Organized prayer was eliminated. Teachers learned to avoid religious references altogether—not always because courts required it in every instance, but because avoiding risk became institutional habit. Over time, this practice of preemptive or “prophylactic” compliance blurred the line between preventing coercion and excluding religion entirely.

It is this enforcement regime, rather than the text of the Constitution itself, that HB1491 seeks to confront.

Under the bill, public schools would be required to teach the Bible as literature and history, including its influence on Western civilization, moral philosophy, and historical development. Instruction is framed as academic rather than devotional, with parents and adult students retaining the right to opt out. While the Supreme Court has long acknowledged that objective study of religion is permissible, many schools abandoned the practice altogether after Schempp. HB1491 attempts to restore biblical literacy as a legitimate and essential component of public education.

The bill also provides for a designated daily opportunity for prayer or the reading of religious texts, including but not limited to the Bible. Participation would be voluntary and based on affirmative consent, with safeguards to ensure non-participants are not exposed or coerced. This approach directly challenges the Warren Court’s reliance on psychological coercion theory by substituting a framework grounded in personal choice rather than presumed pressure.

Perhaps most consequentially, HB1491 limits when school officials may enforce separation-of-church-and-state doctrine or Establishment Clause restrictions. Under the bill’s framework, officials may do so only when required by a binding court order or a directly applicable Supreme Court ruling. This reverses decades of preemptive restriction. Instead of barring religious expression out of fear of litigation, schools would be required to allow it unless expressly prohibited.

The legislation also restructures legal incentives by allowing individuals to sue officials who improperly restrict religious expression while imposing attorney-fee liability on unsuccessful Establishment Clause challenges. The effect is to shift legal risk away from schools that accommodate religious expression and toward those who seek to challenge it, fundamentally altering how constitutional disputes in education are litigated.

HB1491 does not overturn Supreme Court precedent. Only the Court itself can do that. What it does instead is challenge the practical dominance of Warren Court jurisprudence by redefining how those decisions are enforced at the state and local level. Where the Warren Court emphasized coercion, HB1491 emphasizes consent. Where courts encouraged caution, the bill mandates accommodation. Where litigation drove policy, the bill reallocates legal risk.

For many families, the absence of biblical literacy and moral context has produced historical and cultural illiteracy. For others, the post-1960s settlement represents not neutrality, but exclusion. HB1491 reflects the view of its sponsors and supporters that decisions shaped by the Warren Court—and catalyzed by activists like Madalyn Murray O’Hair—should no longer define public education without challenge.

Truthwire News reached out to Representative Bulso for comment, and he had this to say:

“For too long, the Supreme Court’s erroneous precedent in Engel v. Vitale has prevented children who attend public schools in the United States from learning about the New and Old Testaments of the Bible. HB1491, if enacted will correct this historical anomaly, and will also return to Tennessee’s public schools’ voluntary vocal prayer, as it existed prior to 1962.”

Whether this effort ultimately reshapes education policy or forces judicial reconsideration, one conclusion is clear: the constitutional settlement forged in the 1960s is no longer treated as beyond question.

TruthWire will continue to follow this bill as it makes its way through the legislative process. Currently, the bill is not yet scheduled with the appropriate committees in either chamber. We will inform our readers when those meetings are on the legislative calendar, so action can be taken.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()