Investigation traces multi-session Tennessee child policy changes, examining how expanding detention, education, and intervention laws reshape parent-state authority and raise new questions about due process, parental rights, and government power.

How Tennessee’s Child Policy Framework Has Been Quietly Expanding — And Why That Raises Questions in a State That Champions Parental Rights

A TruthWire Investigation into Family Authority, State Power, and Tennessee Law

(TruthWire Investigative Series — Part 1)

A parent rarely imagines that the most powerful decisions about their child could one day be made in rooms they never enter—courtrooms, administrative offices, classification hearings, or contractor-run facilities operating under state authority. Most families move through life assuming the parent-child relationship is the primary unit of authority, protected culturally and legally. In Tennessee, a state that frequently emphasizes conservative values like parental rights, limited government, and individual liberty, that assumption feels especially strong.

One of the most significant concerns surrounding parental rights legislation is the growing pattern of Tennessee law recognizing parental rights — but only up to a point. In practice, this creates a framework where parental authority is treated as conditional rather than fundamental. The long-term implication of this approach is the gradual erosion of those rights through policy exceptions, regulatory carve-outs, and state intervention thresholds, raising serious questions about whether parental rights remain substantive protections or are slowly being reduced to permissions granted — and potentially revoked — by government authority.

But when you step back and examine the trajectory of child-related policy over the last several legislative cycles, a larger question begins to emerge: when did the balance begin shifting—and why?

This story did not begin this session.

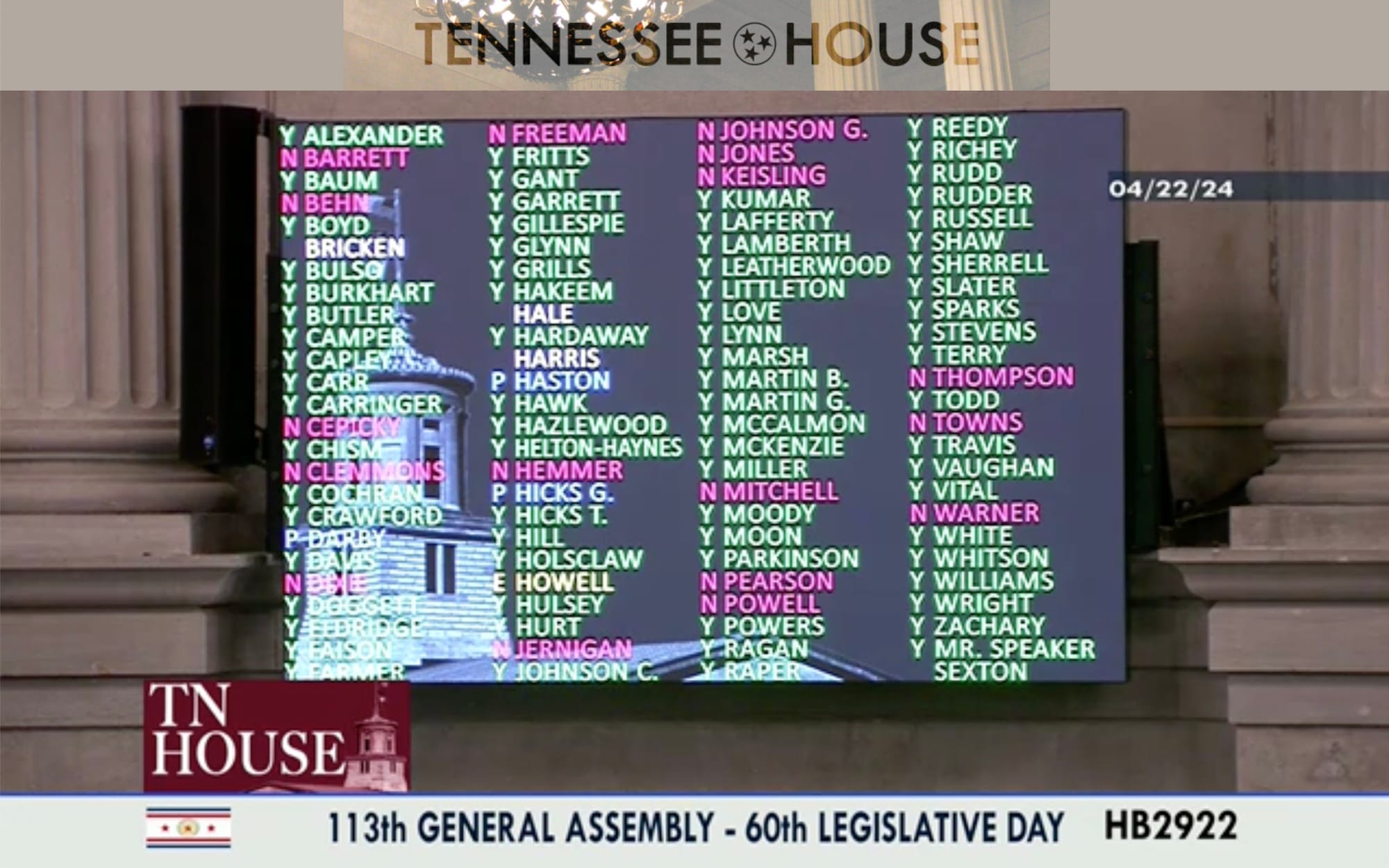

It did not begin with Senate Bill 1868. It did not begin with recent debates about juvenile detention thresholds, classification authority, or expanded definitions of supervision. The pattern can be traced back through prior sessions, including the passage of House Bill 2922 in 2024 after significant legislative maneuvering and amendment restructuring. That bill, originally introduced as a caption bill, evolved into legislation allowing the creation of residential “opportunity” charter school environments for certain categories of at-risk youth—including populations that can overlap with students experiencing disabilities, behavioral challenges, or socioeconomic hardship.

During debate on HB2922, policy experts and disability advocates raised concerns about potential institutional commingling, parental authority erosion, and lack of clear guardrails protecting students with special needs. The bill ultimately passed, but it left behind a policy footprint worth examining: expanding state-directed placement authority over minors under certain conditions.

That bill passed with a bi-partisan 75 voting yes, 17 no's, and 3 present not voting.

Fast forward to current legislation like SB1868, which proposes adding a new classification category: “child in need of heightened supervision.”

To understand why that matters, you must look at the law it modifies.

Under current Tennessee Code § 37-1-114, detention of a minor prior to adjudication is supposed to be limited to specific circumstances: probable cause of delinquency, immediate threat to safety, or risk of flight. Even then, the statute emphasizes that detention should only occur if no less restrictive alternative exists.

SB1868 does not remove those standards outright. Instead, it adds a parallel classification pathway. A child could potentially be classified based on exhibited or threatened behavior consistent with certain violent offense categories—even if no delinquency petition has been filed, and even if the child is legally incompetent to stand adjudication.

From a legal structure standpoint, that represents an expansion of state discretion. Not necessarily guilt. Not necessarily conviction. But classification authority.

That distinction matters.

Because classification systems tend to operate differently than adjudication systems. One is rooted in proving an act occurred. The other is rooted in evaluating risk, behavior patterns, or predictive models.

And that is where larger policy questions begin to surface.

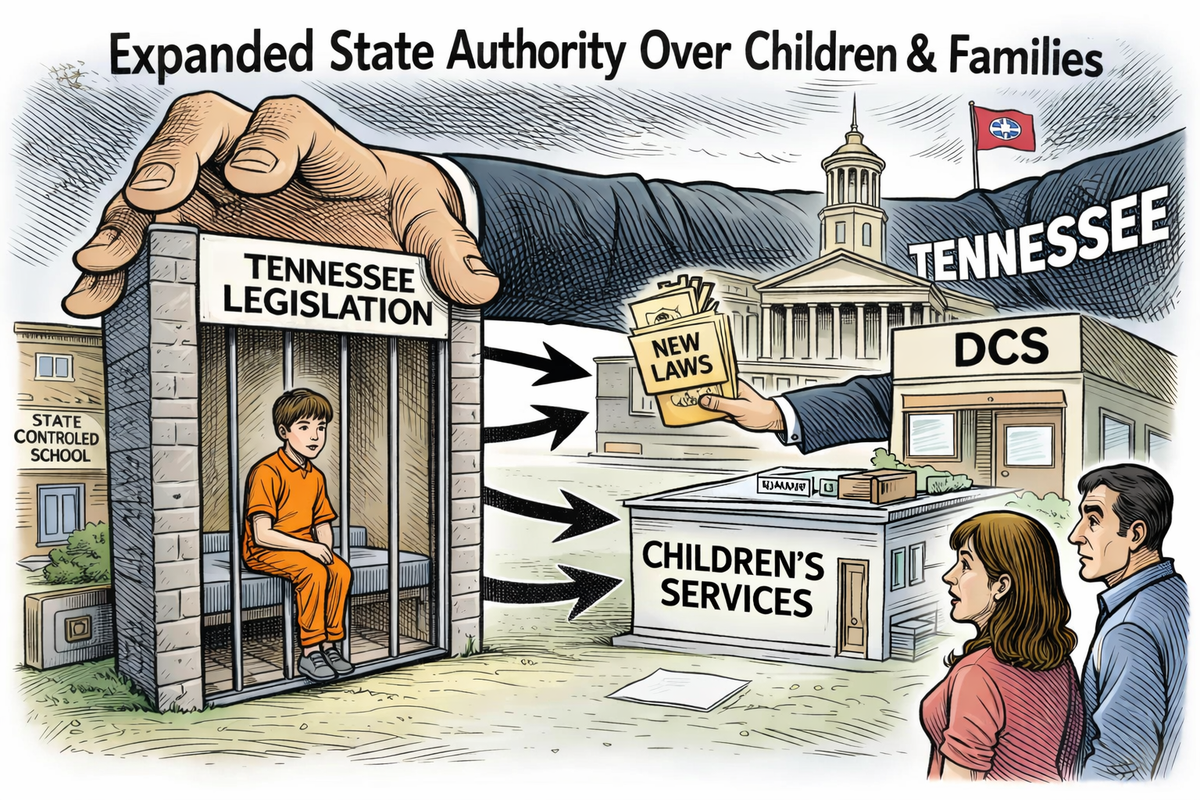

Across multiple sessions, Tennessee has seen policy proposals or enacted laws that incrementally expand:

· Classification categories

· State custody eligibility definitions

· Institutional placement pathways

· Duration of state supervisory authority

· Liability frameworks surrounding state contractors

· Programmatic funding tied to child placement and service delivery systems

None of these, standing alone, necessarily signals a systemic shift. But taken together, they begin to form a pattern worth asking about.

Particularly when viewed alongside the growing ecosystem of publicly funded service providers operating within the child welfare and juvenile systems. Tennessee contracts with a network of nonprofit and for-profit providers that deliver foster care, residential services, therapeutic programs, and transitional housing for youth aging out of state custody. Public reporting shows major contractors receiving tens or hundreds of millions annually through combinations of state contracts, federal grants, Medicaid funding, and federal program reimbursements.

That reality alone does not imply wrongdoing. States require service providers. Vulnerable children require services. But it does raise governance questions any taxpayer—and any parent—has a right to ask:

· How does policy design interact with funding structure?

· How does classification expansion interact with placement capacity?

· How does liability law interact with contractor behavior incentives?

· And how does all of this interact with parental authority?

Tennessee frequently positions itself as a national model for conservative governance—emphasizing local control, family autonomy, and skepticism toward centralized authority. Which makes the policy trajectory worth examining through that same lens.

· If a state prioritizes parental rights, should classification systems expand faster than adjudication protections?

· If a state prioritizes limited government, should detention or custody pathways expand through administrative definitions rather than criminal findings?

· If a state prioritizes fiscal responsibility, how should taxpayers evaluate the rapid growth of child-services contract ecosystems?

These are not accusations. They are governance questions.

Supporters of expanded authority often frame it through public safety and early intervention. Critics often frame it through civil liberties and parental autonomy. Both frameworks can exist simultaneously. The role of investigative reporting is not to assign motive—it is to identify patterns and present the public with information necessary to evaluate policy direction for themselves.

What is clear is this: Tennessee’s child policy framework is not static. It is evolving. And it has been evolving for multiple legislative cycles—not just this one.

Understanding that history matters. Because policy shifts rarely occur in single moments. They occur through cumulative change—definition expansions, threshold adjustments, authority clarifications, funding structure alignment, and enforcement framework updates.

The question now is not whether change is occurring.

The question is whether Tennesseans—particularly parents—fully understand the direction of that change.

Series Note: What Comes Next

This is the first article in an ongoing TruthWire investigative series examining how child-related policy has evolved across multiple Tennessee legislative sessions—and what those changes could mean for families, students, and taxpayers.

In upcoming articles, we will examine:

· How classification pathways differ from adjudication pathways

· How detention timelines and custody authority have evolved

· Why special needs students may face unique vulnerability inside behavior-based classification systems

· How contractor ecosystems, funding streams, and liability frameworks intersect with policy design

· What transparency and accountability should look like in a system serving the state’s most vulnerable children

The goal is not to tell Tennesseans what to think.

The goal is to make sure they have enough information to ask better questions.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()