Final chapter of The Slow Shift reveals how policy definitions, funding streams, contractor systems, and enforcement structures combine to reshape family authority. Readers are urged to contact legislators and demand transparency and guardrails now!!

(TruthWire Investigative Series — Conclusion)

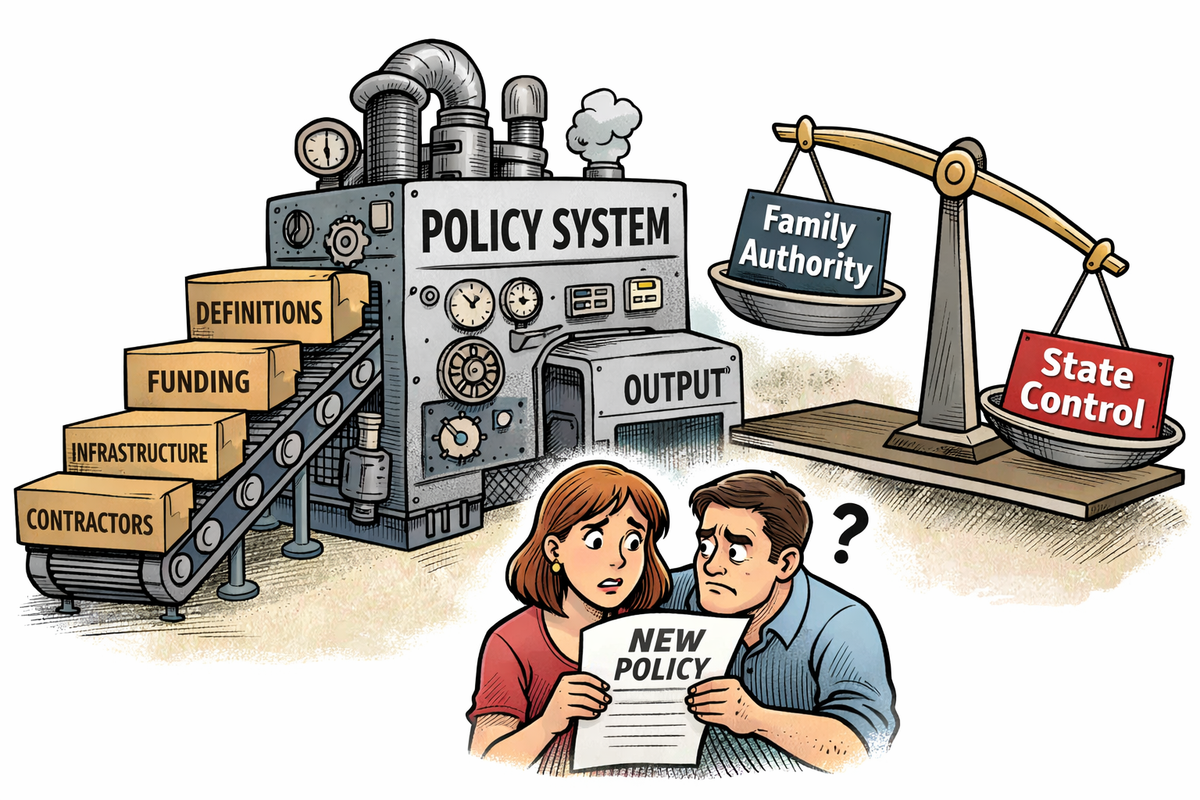

Over the past week, this series has examined a question that rarely receives sustained public attention: how do major shifts in the relationship between families and government actually occur? The first five articles focused on pattern recognition. They explored how public policy rarely changes through a single dramatic law or headline moment. Instead, it evolves incrementally through expanding definitions, growing funding streams, infrastructure investments that operate outside public visibility, and classification authority that moves earlier into children’s lives.

Each article asked readers to step back from political messaging and instead examine how systems are built over time. The goal was not to predict outcomes or assign motive, but to show how language, funding, infrastructure, and enforcement historically develop together in public systems. Those early pieces established the pattern. This final chapter completes the picture by bringing forward the deeper structural layer that often remains invisible in public-facing policy debates: what happens when those elements converge into permanent operational systems.

For most Tennessee families, government systems that serve vulnerable children feel distant and limited to extreme circumstances involving abuse, criminal conduct, or severe crisis. However, public policy rarely changes through sudden transformation. More commonly, change occurs through technical adjustments to definitions, funding eligibility, classification authority, infrastructure development, and enforcement design. Over time, these incremental adjustments can significantly expand how and when state systems interact with families.

At the legal level, Tennessee juvenile authority operates primarily under Title 37 of the Tennessee Code, which governs juvenile courts, detention authority, and child welfare intervention powers. Tennessee Code § 37-1-114 continues to establish thresholds tied to probable cause, immediate danger, or adjudicated conduct before detention can occur.

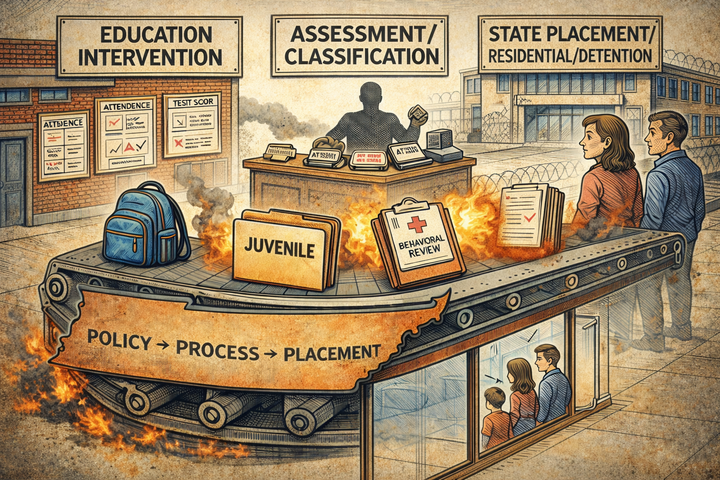

Those statutory guardrails remain in place. However, recent legislative proposals and policy discussions have increasingly introduced parallel classification pathways, including categories tied to heightened supervision or behavioral risk indicators. These frameworks can expand when and how youth are evaluated and routed into state systems earlier in the intervention process.

Education and placement policy has also expanded through legislation tied to alternative or opportunity-based educational models, increasing infrastructure capacity for students identified as “at-risk” across academic, behavioral, and environmental indicators.

Individually, these policies are often framed as intervention tools. Structurally, however, expanded definitions tend to expand the population eligible for system contact. In many public policy systems, definition expansion is the first step toward capacity expansion.

The significance of capacity expansion becomes clearer when examined alongside the funding architecture supporting youth services nationwide. Much of the child welfare and youth placement ecosystem operates through blended federal and state funding streams, including foster care reimbursement programs, transition-to-adulthood programs, and Medicaid reimbursement structures tied to behavioral health and residential treatment services.

These funding streams exist to ensure vulnerable children receive services. However, they also create permanent funding channels that support long-term infrastructure, staffing, and program capacity. Public policy research across multiple sectors has shown that once fixed infrastructure exists, systems often develop incentives to maintain utilization in order to sustain operational funding and workforce stability.

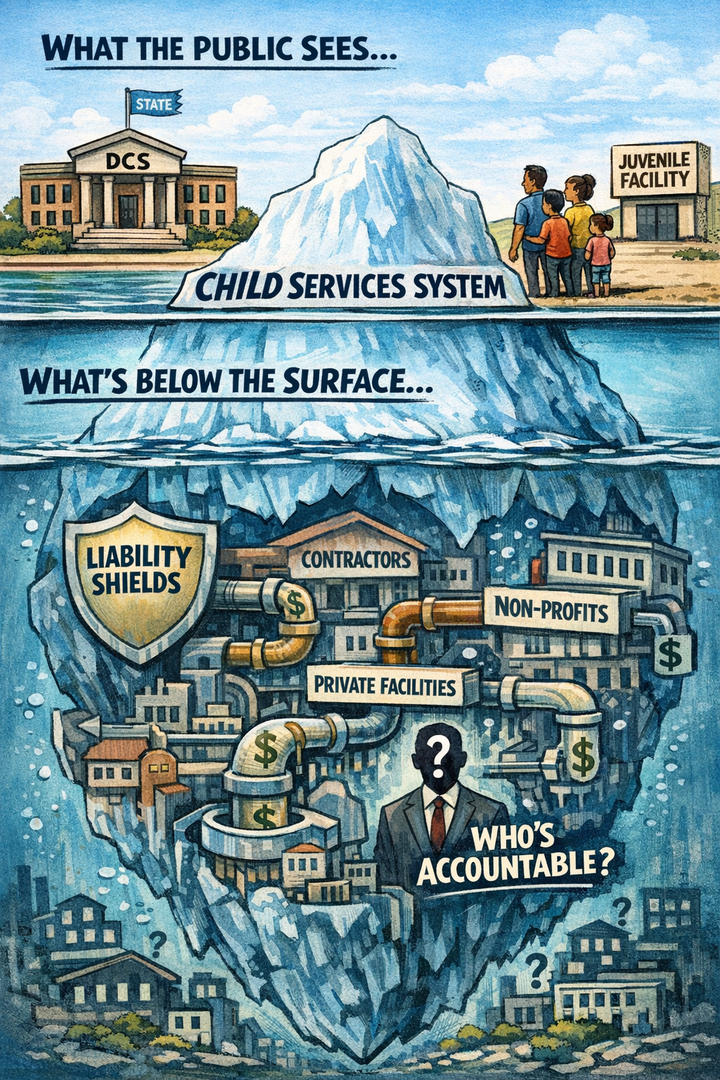

The contractor ecosystem operating inside youth services adds another layer to how laws are experienced by families. Tennessee relies heavily on nonprofit and private service providers funded through state contracts, federal pass-through programs, Medicaid reimbursement, and grant funding. Public nonprofit disclosures and financial filings demonstrate significant revenue and asset growth among major service providers operating within the child welfare and youth placement ecosystem, largely tied to public funding streams.

None of these data points independently demonstrate wrongdoing or malicious intent. However, they do illustrate the size and permanence of the public-private infrastructure operating inside child services delivery. Policy debates surrounding contractor liability protections reflect this structural tension.

For families, the most important distinction is not how policy is written, but how policy is applied. Families rarely experience legislation when bills pass. They experience policy months or years later when a school initiates a referral, when a juvenile intake officer makes a classification decision, when a contractor performs a risk assessment, or when a judge applies a statute written years earlier to a child standing in a courtroom.

Recent policy trends have not necessarily removed statutory protections. Instead, they have increasingly introduced parallel intervention pathways that expand when and how systems can enter family decision-making earlier in the process. Individually, each pathway can be justified. Collectively, they expand entry points into state oversight systems.

Families raising children with disabilities, trauma histories, neurological conditions, or behavioral regulation challenges face unique exposure to classification-based intervention systems. Behavioral presentation can overlap with risk classification triggers. Without explicit disability-informed guardrails, systems designed to identify high-risk behavior can unintentionally capture children whose behavior is rooted in developmental or neurological conditions. This outcome is often not the result of malicious actors but rather a result of system design.

The central question throughout this series has never been whether Tennessee wants to protect children. That goal is universal. The question is how protection is defined and who holds primary authority when state protection models intersect with parental rights frameworks. If legislative trends simultaneously expand classification authority, intervention discretion, contractor service ecosystems, and infrastructure capacity, Tennessee voters must determine how those expansions align with commitments to parental authority, limited government, and individual liberty.

Once laws are passed, enforcement, rather than legislative intent, determines how families experience policy. Once systems are built, they rarely shrink without deliberate policy correction.

This series set out to show readers how slow structural change works. At this point, the pattern and the underlying system structure are both visible. What happens next depends on whether citizens engage while systems are still evolving.

Citizens who believe in parental rights, family authority, and transparent government oversight should consider contacting their state representatives and state senators to ask direct questions about classification authority, infrastructure expansion, contractor accountability, and how these systems are reviewed, measured, and limited once established.

The long-term balance between family authority and state authority will not be determined by a single bill. It will be shaped by whether citizens engage while systems are still being built.

This is the final chapter of this series. The information is now public. What happens next will be determined by what citizens choose to do with it.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()