Tennessee policy changes are expanding how children can enter state supervision systems before delinquency adjudication. This investigation examines classification thresholds, detention authority, and how evolving juvenile law may reshape family-state boundaries.

How Tennessee’s Expanding “Supervision” Language Could Quietly Reshape the Parent-Child Relationship

(TruthWire Investigative Series — Part 2)

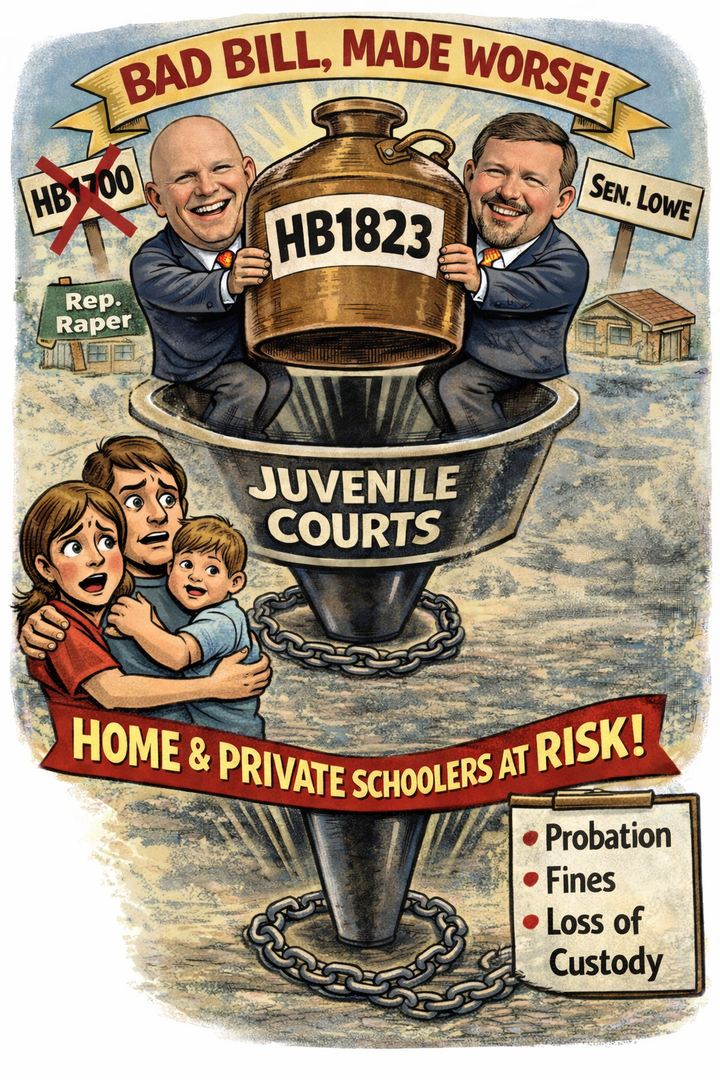

If Article One established anything, it is that major policy shifts almost never arrive all at once. They arrive quietly — through definitions, thresholds, and administrative language that sounds procedural but carries real-world authority. Tennessee did not wake up one morning with a radically different juvenile system. Instead, over multiple sessions, the state has layered new categories, new pathways, and new intervention authorities into existing law. None of them individually appear dramatic. Together, they begin to tell a story.

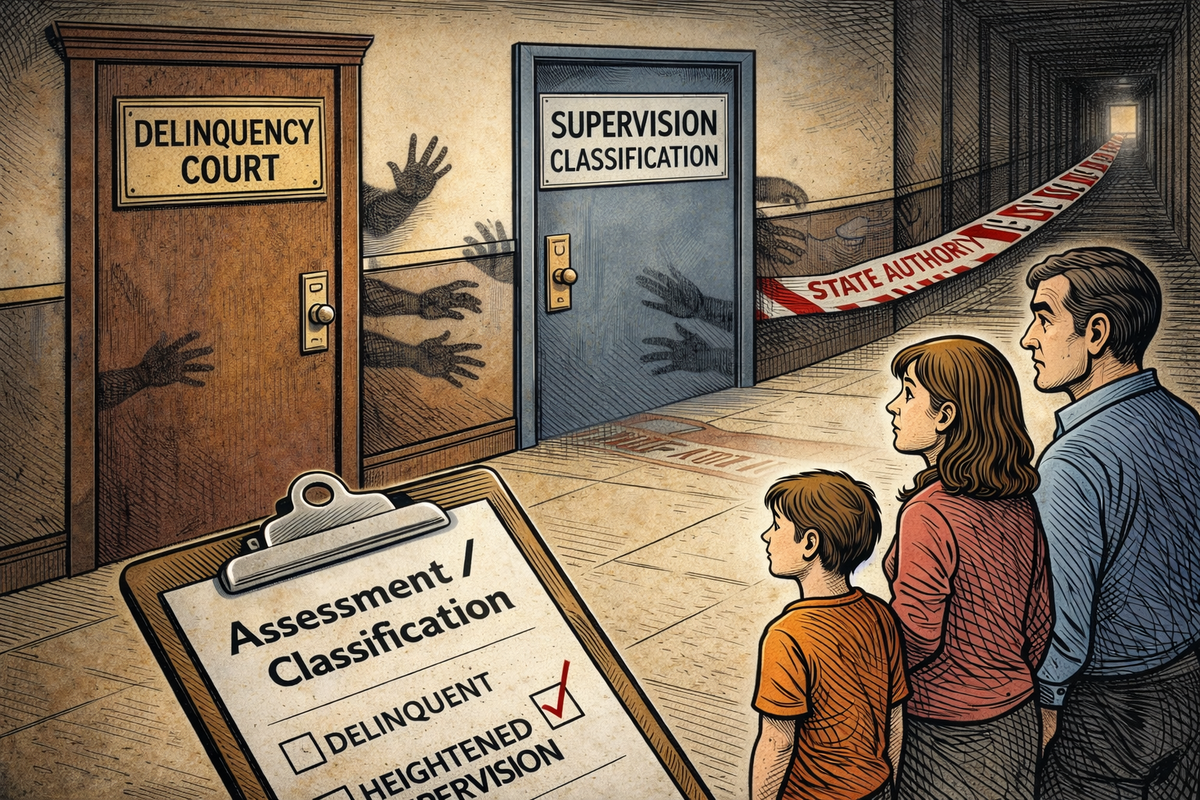

At the center of that story is a simple but powerful shift: the movement away from intervention based strictly on adjudicated delinquency, and toward intervention based on behavioral classification.

Under existing Tennessee law, the state’s authority to detain a child prior to a hearing is intentionally narrow. The statute is written to reflect a long-standing legal principle that government should not remove liberty — especially from minors — without clear procedural cause.

That law lays out guardrails. A child can generally only be detained if there is probable cause that a delinquent act occurred, or if there is an immediate threat to safety, or if there is a flight risk and no less restrictive alternative exists. Even children categorized as “unruly” are typically subject to strict time limits — usually measured in hours or days, not months — before a hearing must occur.

In other words, the traditional model is built around sequence. Allegation. Hearing. Determination. Then intervention. That structure matters because it places the courts — and due process — between families and state custody authority.

But recent legislative language begins to introduce something structurally different. Consider the proposed addition of the category “child in need of heightened supervision,” introduced in legislation like SB1868.

On paper, that language sounds preventative. It sounds protective. It suggests early intervention before harm occurs. And in many policy environments, preventative language is introduced with exactly that goal.

But structurally, it also opens the door to a different decision sequence — one that begins not with a proven act, but with an assessment of behavior, threat perception, or risk modeling. Instead of moving through a criminal-style adjudication pipeline, systems begin to move through classification pipelines. Assessment leads to categorization. Categorization leads to supervision authority. Supervision authority can then lead to placement, monitoring, or custody expansion.

None of that automatically implies misuse. But it does change where power sits in the system.

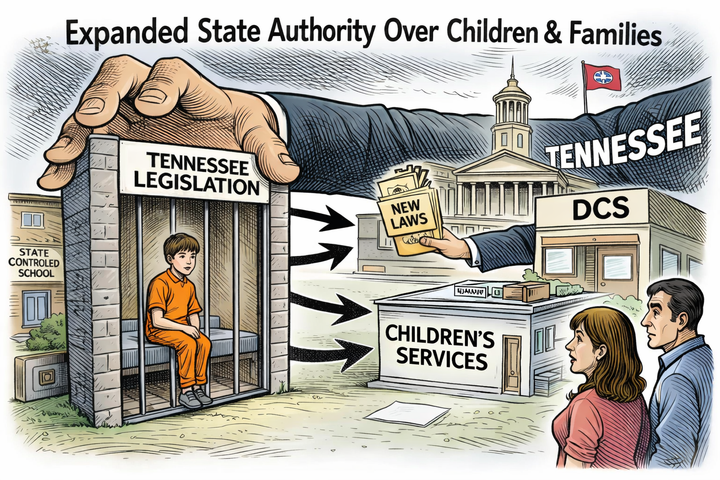

This becomes especially important when viewed alongside other legislation passed or proposed in recent years. For example, the 2024 passage of HB2922 created a framework for expanded educational and residential options tied to “at-risk” classifications.

The “at-risk” definition is broad by design. It includes students who are chronically absent, academically behind, previously detained, exposed to abuse or neglect, struggling with substance exposure, or coming from economically disadvantaged households. Many of these factors are real and serious. Many represent students who absolutely need support.

But many of these same indicators also statistically overlap with disability populations, trauma-impacted students, and neurodivergent children — populations who often display behavioral markers without criminal intent or delinquent behavior.

Again, this is not an accusation about legislative intent. It is a structural observation about how classification frameworks function in real-world systems. When definitions broaden, entry points broaden. When entry points broaden, the number of children eligible for intervention grows — even if the original goal was targeted support.

For a state that consistently identifies itself as strongly conservative, strongly pro-family, and strongly committed to parental rights, this creates a natural policy questio If Tennessee’s public policy philosophy is rooted in parental authority and limited government intrusion, how does the state ensure that expanding behavioral classifications do not unintentionally move decision-making authority away from families and toward administrative systems?

This question becomes even more important when viewed through the lens of system incentives. Tennessee, like every state, operates a complex network of child services, educational intervention programs, residential placement providers, and contracted support organizations. These systems are necessary. They provide real services to real children in crisis. But they also require funding, infrastructure, and utilization thresholds to operate effectively.

As classification definitions expand, placement eligibility can expand. As placement eligibility expands, system utilization expands. This creates a policy environment where lawmakers must be especially careful to ensure that classification thresholds remain tightly tied to objective risk, not subjective behavioral interpretation.

Families often assume state intervention only happens after criminal behavior or court conviction. But modern juvenile policy increasingly operates upstream — at the point of risk assessment, behavioral categorization, and preventative supervision. That shift can be positive when guardrails are strong. It can be dangerous when definitions are vague.

All of this analysis naturally leads to several important questions for those who vote Republican, with the expectation that voting republican leads to conservative policy outcomes.

If Tennessee is truly committed to parental rights and limited government intrusion, what safeguards must exist when classification authority expands? Should parents be guaranteed legal standing at the classification stage? Should disability differentiation language be mandatory before behavioral risk categories can trigger custody or placement decisions? Should supervision authority expansions require independent judicial review earlier in the process?

These are the kinds of questions conservative governance philosophy traditionally encourages. Questions about power concentration. Questions about state scope. Questions about unintended consequences of administrative authority expansion.

Over the last several legislative cycles, Tennessee has gradually expanded custody definitions, placement authority pathways, behavioral risk classification language, and supervisory flexibility timelines. None of these changes alone define a direction. But together, they begin to shape a trajectory — one that deserves public understanding and public discussion.

Because policy shifts rarely announce themselves. They accumulate. And by the time the public sees the full system impact, the legal architecture is already in place.

This series exists for one reason: not to tell Tennesseans what to think, but to make sure Tennesseans understand how policy structure actually works — especially when it involves children, families, and the balance of authority between parents and the state.

In Article Three, we will move deeper into how detention timelines, allegation-based holds, and supervision classifications intersect — and how time itself can become one of the most powerful tools in a juvenile system, especially when classification replaces conviction as the trigger point.

Next, TruthWire will examine how “at-risk youth” education policy, residential school models, and placement authority intersect — and what happens when education systems and supervision systems begin to overlap.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()