Cybersecurity experts warn voter rolls shape elections long before ballots are cast, yet receive far less scrutiny than voting machines.

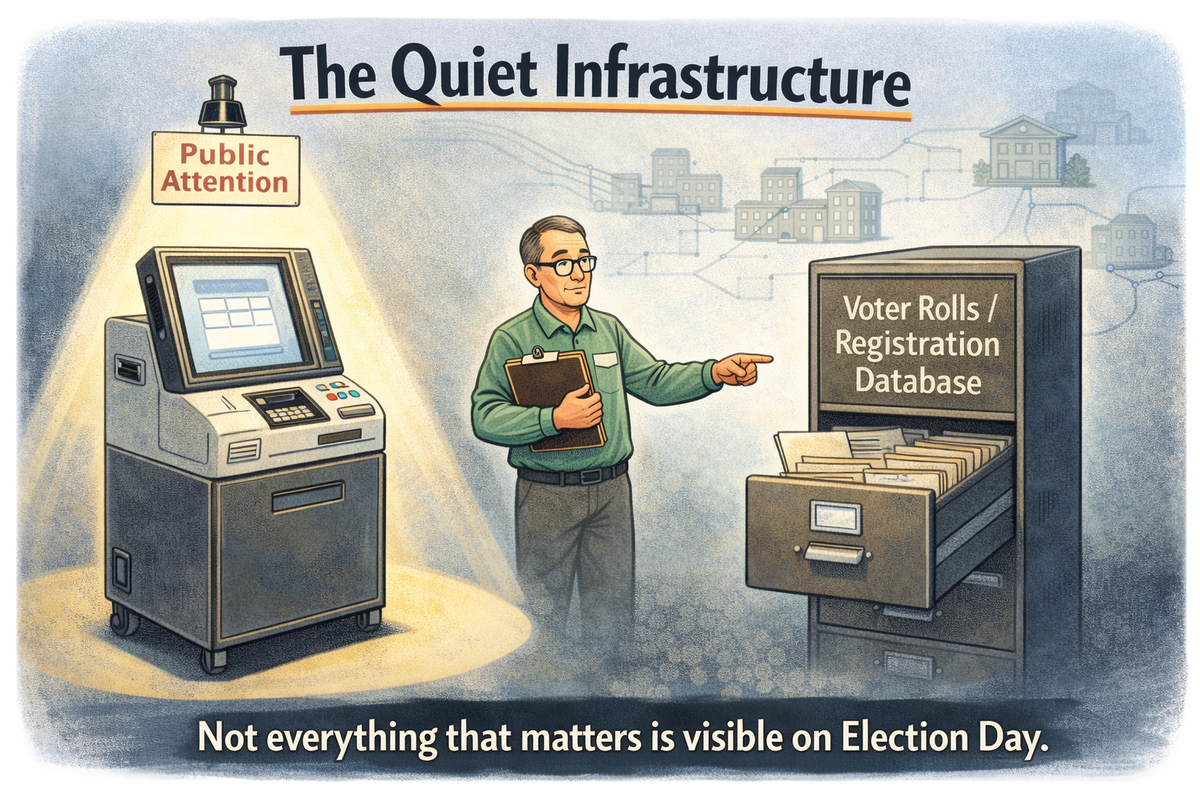

When election security is discussed publicly, the conversation almost always centers on voting machines. Images of tabulators, memory cards, and ballot scanners dominate hearings and headlines. These systems are visible. Voters interact with them directly. They are easy to point to when concerns arise.

But cybersecurity experts have long cautioned that focusing exclusively on voting machines overlooks a quieter—and in some ways more consequential—layer of election infrastructure: voter registration databases and voter roll management systems.

Long before a ballot is cast, voter rolls determine who is eligible to vote, where they vote, and how their registration is verified at polling places. These systems are updated year-round, accessed during early voting and on Election Day, and integrated into broader election management processes. For cybersecurity professionals, that combination alone warrants serious attention.

This is not a claim about any specific system in Tennessee. It is a principle widely recognized across cybersecurity disciplines: systems that are networked, continuously updated, and connected to downstream processes require rigorous oversight, documentation, and verification.

Cybersecurity researcher J. Alex Halderman, a professor at the University of Michigan, has spent years studying election infrastructure. In controlled demonstrations, Halderman has shown how election-related systems can be affected by malware, misconfiguration, or weaknesses in process controls. One such demonstration is publicly available here.

These demonstrations are often misunderstood. They do not claim that elections are routinely compromised. They do not assert that specific jurisdictions have been hacked. Instead, they illustrate how vulnerabilities can exist in complex systems even when administrators act in good faith.

A central lesson from this research is that election outcomes can be influenced without altering votes directly. In many scenarios, the risk lies upstream—in the systems that determine voter eligibility and access.

If a voter arrives at a polling place and is told they are not on the rolls, the impact is immediate. If a voter is directed to the wrong precinct, their ballot may not count. If registration records are outdated or inconsistent, election officials may face challenges reconciling turnout after the fact. None of these outcomes require tampering with a voting machine. They require only changes or errors in records.

National case studies provide context for why experts emphasize this layer of election administration. In New Jersey, election officials acknowledged that a software error affected vote tallies in a local school board race, ultimately leading to a recount that reversed the initially declared outcome. Coverage of that incident can be found here.

Supporting documentation from election integrity researchers further details how the error occurred and how it was discovered during the recount process.

The New Jersey case does not suggest malicious intent. It underscores a different point: complex systems fail, sometimes quietly, sometimes without immediate detection. When failures occur, transparency and auditability are what preserve public trust.

Voter registration databases present additional challenges because they are inherently dynamic. People move. People die. Names change. Records must be updated across jurisdictions that do not always share data seamlessly. Even well-maintained databases can accumulate outdated entries over time.

Most of those records never result in improper voting. But from a security and integrity perspective, outdated or duplicate records increase complexity—and complexity is the enemy of resilience.

Experts also point to how voter registration systems interact with other election infrastructure. In many jurisdictions, data collected at vote centers or precincts is transferred back to central election offices for reconciliation and reporting. Those transfers may involve removable media, local networks, or centralized election management systems.

Cybersecurity professionals consistently note that the most vulnerable moments in any system often occur during data transfer and integration, not during steady-state operation. That observation applies broadly across industries, not just elections.

Some election infrastructure relies on virtual private networks, or VPNs, to protect data in transit. VPNs can be an important security tool, but experts caution that they are not a comprehensive solution. VPNs encrypt data moving between systems, but they do not protect endpoints, detect malware already present, or replace logging, monitoring, and independent audits.

Research examining the limitations of VPN-based security in election contexts is summarized here.

Other analyses have documented how vote centers and associated systems could be affected by data breaches if layered safeguards are not in place.

Again, these sources do not claim that Tennessee systems are vulnerable. They explain why cybersecurity professionals advocate for defense-in-depth—multiple overlapping safeguards—and for independent verification of those safeguards.

In sectors such as banking, healthcare, and utilities, systems that manage sensitive data are subject to rigorous documentation, periodic assessments, and third-party audits. Those practices exist not because organizations are presumed untrustworthy, but because verification is how trust is maintained.

Elections occupy a unique position. Officials are understandably cautious about disclosing technical details that could be misused. At the same time, the absence of high-level documentation can make it difficult for the public to distinguish between necessary security discretion and a lack of transparency.

This is where the tension lies.

Cybersecurity is not about guarantees. It is about process—how systems are designed, how they are monitored, how issues are detected, and how they are corrected. Demonstrating that process does not require exposing vulnerabilities. It requires showing that safeguards exist and are evaluated.

Importantly, nothing in the research reviewed for this series establishes that Tennessee’s voter registration systems have been compromised. No evidence examined suggests that voter rolls were altered improperly or that elections were affected.

The issue is not proof of failure. It is the absence of publicly available information demonstrating how risk is managed.

For voters, the question is not whether systems are perfect. No system is. The question is whether the public can see enough of the process to reasonably understand how integrity is protected.

When that information is unavailable, concern is not alarmist. It is rational.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()