The fundamental idea of American governance is the limitation of government to specific authority. Do politicians care about this? A quick look at Tennessee politics gives a grim answer....

The principle of constitutionally limited government might as well not exist, to hear most politicians talk. The question is not ‘What do I have the authority to do?’ but ‘What do I have the power to do?’ We’ve seen this from the US Supreme Court, with cases such as Roe v Wade, where the court made the laughable finding that the Constitution’s ‘penumbra’ guaranteed privacy rights for doctors performing abortions based on the woman’s trimester. Whether for ideological-theological or economic reasons or simply for the love of power, politicians seem ever more interested in what they can do, regardless of what they should do. Tennessee state politics are no exception.

The Tennessee state constitution directs the legislature is to create a public school system (Page 24). The only other mentions of education in the current Tennessee Constitution are limitations on the use of lottery money (a moral question of its own) and a tax provision. Article XI, Section 12, therefore, is the basis of Tennessee’s state education system, in a legal sentence. It reads as follows:

“The State of Tennessee recognizes the inherent value of education and encourages its support. The General Assembly shall provide for the maintenance, support and eligibility standards of a system of free public schools. The General Assembly may establish and support such postsecondary educational institutions, including public institutions of higher learning, as it determines.” (Page 24)

Nowhere in this text, we observe, is a general grant of power to create pre-secondary educational institutions given. Consider each sentence in turn. The first sentence provides the rationale for the rest; it does not and cannot grant powers, being entirely indicative of the perspective the state is said to hold institutionally, not its ability to act. If I said, “I recognize and encourage your consumption of cake,” I am not thereby asserting a right in myself any power with respect to your cake-eating. I am instead indicating my intention in using the powers I have, whatever they are, for the purpose of supporting said consumption.

The second sentence does empower the government to create a “system of free public schools.” The term ‘public’ here can be taken either to indicate their governmental nature, as per Article II, Sections 21 and 24, or their openness to the general populace whose voices are component to that government (citizens), as per Article I, Section 9, and Article XI, section 15. In fact, both are true; these are government-defined schools open to the public, ruled by funding and regulation from the state legislature.

The third sentence (the last) grants to the government the power to “establish and support” postsecondary education institutions to the extent of its preference. This power is broad, though not fully regulatory unless it is interpreted as allowing the government to ‘support’ a postsecondary institution contrary to that institution’s agreement, but also sharply limited. The government’s broad ‘establishment’ right is for postsecondary institutions only.

We’ve established what powers the section does grant; let’s consider now what it does not grant.

First, the section does not give the state government regulatory power over the education of its citizens in general. Compulsory attendance laws and curriculum standards for those not funded by the state both fall into this category. Notice that the state government is not told to ‘support’ education. No, it is told to ‘encourage the support’ of education. We could take ‘encouragement’ as referring to punitive actions to ‘encourage’ parents to educate their kids by prodding them with the metaphorical gun barrel. Such interpretation, however, strains credulity. If this was the intent, why does the Constitution not speak more plainly? Perhaps there is a reason that the first compulsory attendance laws in Tennessee came 35 years after the 1870 constitution currently authoritative.

If we look at the language of the 1834 constitution, which addresses education at more length, we find similar, if more prolix, language introducing the relevant article: “Knowledge, learning and virtue, being essential to the preservation of republican institutions, and the diffusion of the opportunities, and advantages of education throughout the different portions of the State, being highly conducive to the promotion of this end; it shall be the duty of the general Assembly in all future periods of this government, to cherish literature and science“ [bolding mine] (Page 18). In the balance, basing compulsory attendance and curricular regulation on this first sentence seems dubious.

The two other sentences provide little more basis for such regulations than the first. I say ‘little’ and not ‘no’ because I see the case that compulsory attendance could be required for government-run institutions, based on the contract entered into when entering them, though that seems a thorny legal issue from my rudimentary understanding of the area. Regardless, neither provides any power to the government to regulate the attendance or curriculum of students who have not availed themselves of its services.

Second and related, this section does not authorize the government to disburse any money in pre-secondary education outside of its own institutions. Strictly speaking, the government using public money for constitutionally unauthorized purposes is theft (in the colloquial sense). As stated before, the provisions of Article XI, Section 12 do not extend beyond the establishing and (in some cases) running of two types of institutions: free pubic schools and postsecondary institutions. The first sentence, however tempting, does not give monetary warrant; like the parallel language in the predecessor constitution (which includes an explicit monetary provision for ‘common schools’), the language here is explanatory, not empowering.

This second limitation brings us neatly back to the assertion I made in the introduction vis a vis government preferring power to authority. I’m referring, of course, to the school voucher system which Gov. Lee, in conjunction with Republican leadership, called an emergency session to pass earlier this year (an emergency session during normal session and several months after the alleged emergency took place).

Now, the school voucher program has so far gone as smoothly as most government programs– which is to say, it’s a bit of a mess, with 166 scholarships ‘accidentally’ awarded and then revoked. It has also attracted some criticism over transparency. Government incompetency is nearly as reliable as death and taxes. The greater issue here is that of principle: where’s the constitutional justification?

The government has the right to establish two types of educational institutions: free public schools and postsecondary institutions. School vouchers, of course, are not the second, being directed towards pre-college education. Are they then ‘free public schools’? Well, given that students operating under the voucher program pay for their tuition (with government money, at least in part), the voucher program can’t be considered a ‘free’ school.

Furthermore, a voucher may be public, but it isn’t a school. In fact, many school vouchers go towards paying for private school tuition. The facts being so, it beggars belief to call school voucher programs ‘free public schools’, except where they are exclusively applicable to said schools as part of the state government’s right to fund said institutions.

Governor Bill Lee does not appear bothered by this. No, he wants, “universal school choice, where every family regardless of their child’s past educational history has access to a scholarship.” Whether he wants universality in the sense of universal basic income, where everybody gets a voucher, I don’t know; the quote is ambivalent, using ‘access to’ rather than ‘use of’. Nevertheless, the thrust is clear: Lee wants school vouchers. He wants them- and he apparently doesn’t care that they’re unconstitutional. At the very least, he hasn’t checked the document which is the basis of his powers.

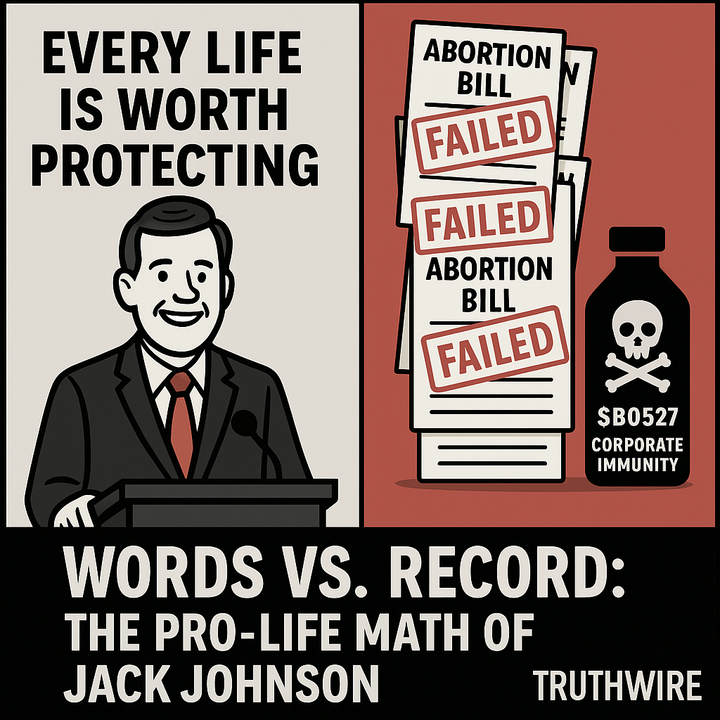

State Senator Jack Johnson, current Senate majority leader (and therefore a man of great influence in state politics), is not better. I’ve seen his campaign flyer touting his school choice record, and his campaign website isn’t shy about it. He dresses it up pretty, I’ll admit, just like he dresses up his crusade to keep Republican primaries open for Democrat voters, and calls school vouchers ‘universal school choice’ rather that ‘education subsidies.’ The essential fact of his support for an unconstitutional measure remains, however.

We have learned over the centuries not to be too optimistic about politicians, but we should not let that make us lax. Preserving the constitutional way of government our forefathers gave us requires vigilance. First, we must not let ourselves forget. When we hear of a government initiative, we shouldn’t just ask, ‘Do I like that?’ We should ask also, ‘Does the constitution give this part of the government this authority?’ We must remember that all powers not given are reserved, as the Tenth Amendment to the federal constitution reminds us. Second, then, we must hold our elected representatives to account and through them hold the unelected representatives to account. We must hold them to the standard of the constitutions they swore to uphold. Only then can we hope to pass down this republic intact to our children and our children’s children.

God bless.

Comments ()