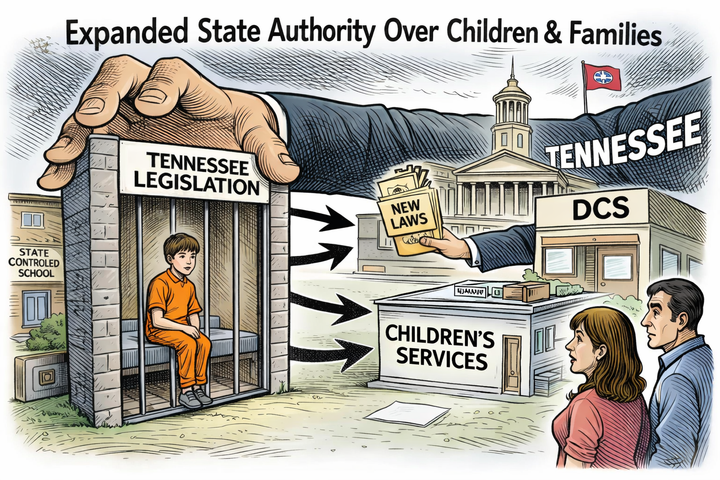

As Tennessee expands child intervention systems, large contractor networks and liability shield proposals raise questions about transparency, oversight, legal accountability, and how family protections are maintained when systems scale.

(TruthWire Investigative Series — Part 5)

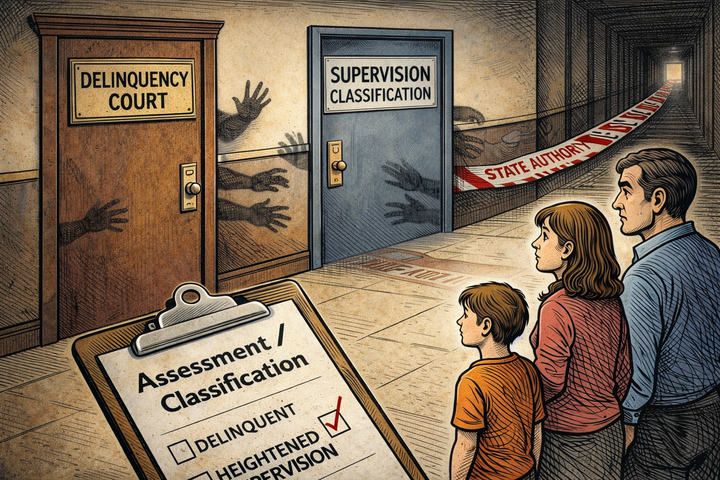

By the time a child enters a state system — whether through education classification, juvenile supervision designation, or child welfare placement — most public attention focuses on the front end. The triggering event. The behavior. The allegation. The crisis moment.

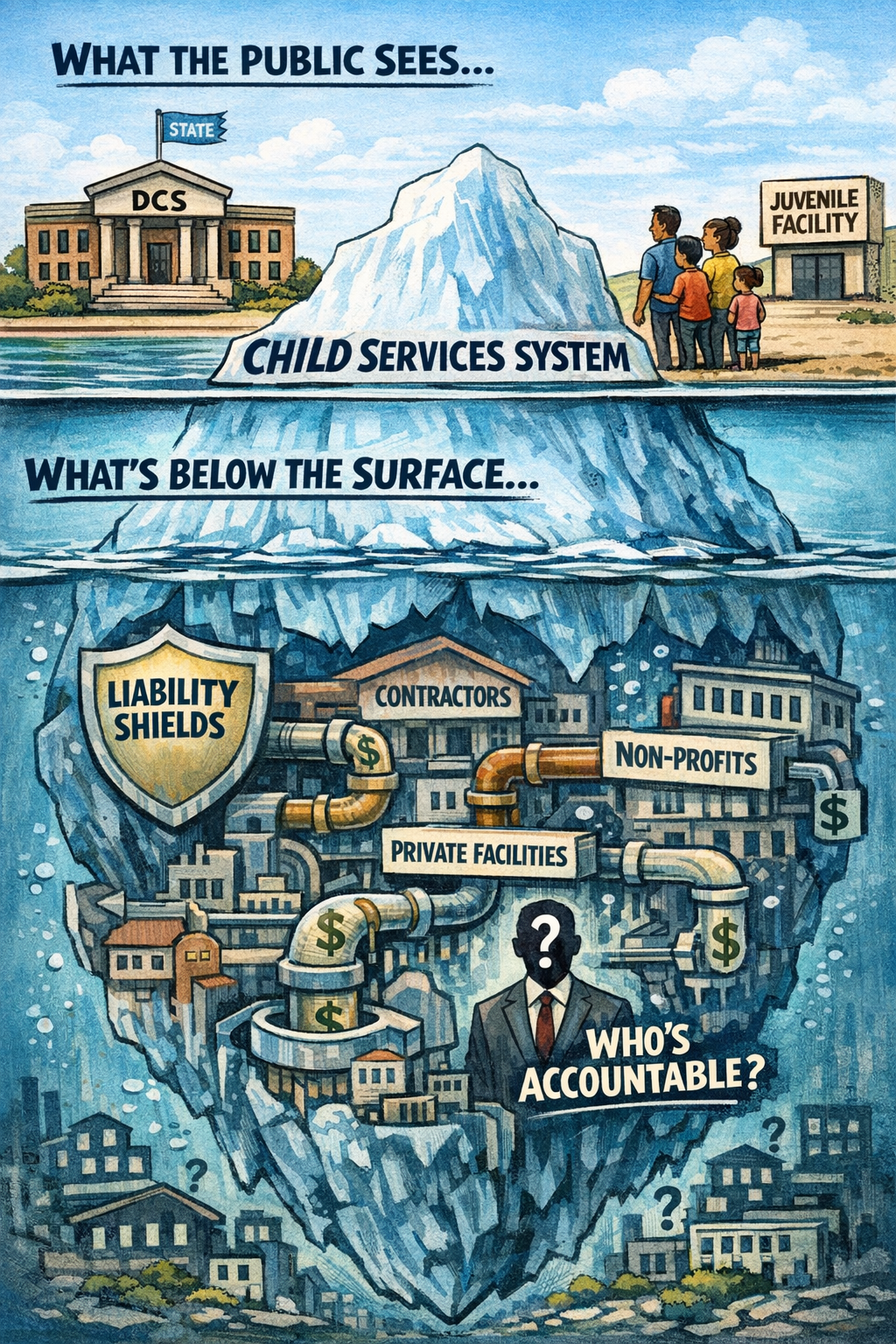

But systems do not stop at entry. Systems require infrastructure. They require staffing, facilities, services, housing, therapy networks, transportation, case management, compliance oversight, and long-term placement structures. And in modern child welfare and juvenile systems, much of that infrastructure is not operated directly by the state. It is operated through a complex network of contracted service providers.

Understanding how those contractor ecosystems function is not about assuming wrongdoing. It is about understanding incentives, scale, and accountability structures — especially when policy expansion increases the number of children who may interact with those systems.

In Tennessee, the Department of Children’s Services (DCS) operates through a network of nonprofit and for-profit contractors providing foster care placement, residential care, transitional housing, behavioral health services, and case support programming. Public records show that some of these organizations operate at very large scale.

For example, public financial reporting shows that Youth Villages, one of the largest child services providers operating in Tennessee, reports hundreds of millions in annual revenue and significant asset holdings. Public filings also show that much of this revenue originates from government contracts, Medicaid reimbursements, and federal program funding streams, with a comparatively small percentage originating from private donations.

Similarly, other large providers, including Omni Visions and related affiliated service entities, operate across multiple service categories, including foster care placement, family services, and transitional support programming.

None of this is unusual in modern child welfare systems. Across the United States, governments rely on contractor networks to provide services at scale. The question is not whether contractor systems exist. The question is how legal accountability is structured when private or nonprofit organizations operate inside public child protection systems.

And that question becomes especially relevant when legislation emerges that modifies liability exposure for those providers.

One example currently drawing policy attention is legislation such as HB1879 / SB1470, which has been discussed in policy and legal commentary as potentially limiting civil liability exposure for certain nonprofit contractors providing services through state child welfare systems.

As of February 12, 2026, the bill has been withdrawn by its sponsors. However, its withdrawal does not erase the fact that it was drafted, introduced, and advanced in the first place. Nor does it answer the broader question this series is examining: in a state that strongly identifies as conservative, why are policies like this being proposed if lawmakers are governing according to those principles?

The stated policy rationale for such protections typically centers on provider stability — the idea that organizations may be less willing to provide high-risk child services if exposed to unlimited liability risk. From a policy design perspective, this is not a novel argument. Similar liability shields exist in medical malpractice caps, foster parent liability protections, and volunteer service immunities in many states.

But the structural question remains: when contractor systems grow in scale, how does accountability scale alongside them?

Because contractor ecosystems do not operate in isolation. They operate alongside funding streams. And funding streams influence system behavior, even when individual providers operate with good faith and professional intent.

Federal child welfare funding structures include reimbursement models tied to placement, services delivered, and case management outcomes. Medicaid behavioral health billing structures often reimburse based on service delivery volume. Housing and transitional support programs frequently receive per-client funding support.

None of this inherently creates perverse incentives. But large-scale systems always raise legitimate public policy questions about incentive alignment.

If funding is tied to services delivered, how do policymakers ensure that the system always prioritizes family preservation when safe and appropriate?

If contractor networks expand capacity — more beds, more programs, more residential facilities — how do policymakers ensure capacity expansion does not subtly shape referral patterns?

If liability shields are expanded, how do policymakers ensure families retain meaningful recourse in cases of negligence, abuse, or failure of care?

These questions are not accusations. They are structural questions that exist in every state operating contractor-driven child services systems.

They become especially relevant when examined alongside policy expansions discussed in earlier articles in this series — expanded classification authority, expanded supervision pathways, and expanded at-risk youth identification frameworks.

Because systems rarely expand in isolation. Classification authority expansion increases potential entry points. Infrastructure expansion increases placement capacity. Funding expansion increases system sustainability.

When all three expand simultaneously, the system becomes more capable of operating at scale.

And scale changes system dynamics.

In Tennessee, public reporting has shown that large child services contractors operate across multiple affiliated organizational structures — nonprofit entities, foundation arms, housing support entities, and service delivery subsidiaries. Again, this is not inherently problematic. Many large service organizations operate similar structures to manage funding streams, compliance requirements, and service specialization.

But structural complexity can reduce public transparency.

And when public transparency decreases, public trust questions increase.

For example, public reporting and policy commentary have raised questions about how nonprofit and for-profit contractor distinctions function when affiliated organizations operate within shared service ecosystems. From a service recipient perspective — the child or family receiving services — the corporate structure often makes little practical difference.

The policy question then becomes: should liability exposure differ based on corporate classification if service delivery and child impact are identical?

Again, this is not an accusation. It is a policy design question.

And it becomes even more complex when examined alongside broader foster care transition systems, including federal programs supporting youth aging out of foster care — programs that provide extended housing support, education assistance, medical coverage, and case management through early adulthood.

These programs exist to protect vulnerable youth during transition to independence. But they also illustrate the scale of funding and service ecosystems surrounding child welfare systems.

Which raises a broader philosophical question — one that cuts across ideology and party affiliation.

If child protection systems expand classification authority, expand infrastructure capacity, and expand contractor network scale simultaneously, how does the state ensure that family preservation remains the primary goal rather than system sustainability?

Because most policymakers, across political parties, publicly state that the goal of child welfare policy is to stabilize families whenever safely possible.

And most voters — particularly in states that emphasize family autonomy and parental rights — expect policy design to reinforce that principle.

So, when legislative sessions include proposals affecting classification authority, detention thresholds, residential placement capacity, and contractor liability structures, it is reasonable for families to ask:

How do these policies work together?

How does accountability scale as system size increases?

How does transparency scale as contractor networks grow more complex?

And perhaps most importantly — how does parental authority remain central in systems designed to intervene in family life?

These are not ideological questions. They are governance questions.

And in systems that operate with both public funding and private or nonprofit service delivery, governance questions are unavoidable.

Because the system behind the system is rarely visible to the public.

But it is always present.

Coming Next in the Series

Article 6: The Economics of Intervention — Facilities, Expansion Funding, and the Long-Term Cost Architecture of Child Services Systems

Because once systems expand — classification, infrastructure, and contractor networks — the final question is sustainability: who funds the system, and how growth changes policy momentum over time.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()