As Tennessee expands behavioral classifications in law, families question whether special needs children could be misidentified. TruthWire examines how policy changes may affect parental rights and state authority.

(TruthWire Investigative Series — Part 4)

As Tennessee expands behavioral classifications in law, families ask whether vulnerable children could be swept into systems never designed for them.

Policy debates around juvenile law and child welfare often focus on intent — protecting children, preventing violence, stabilizing vulnerable families, or intervening earlier to stop crisis escalation. Those are goals few would publicly oppose. But public policy is ultimately measured not by stated intent, but by real-world impact. And when risk-based classification systems expand, one question becomes unavoidable: which children are most likely to be captured by those systems first?

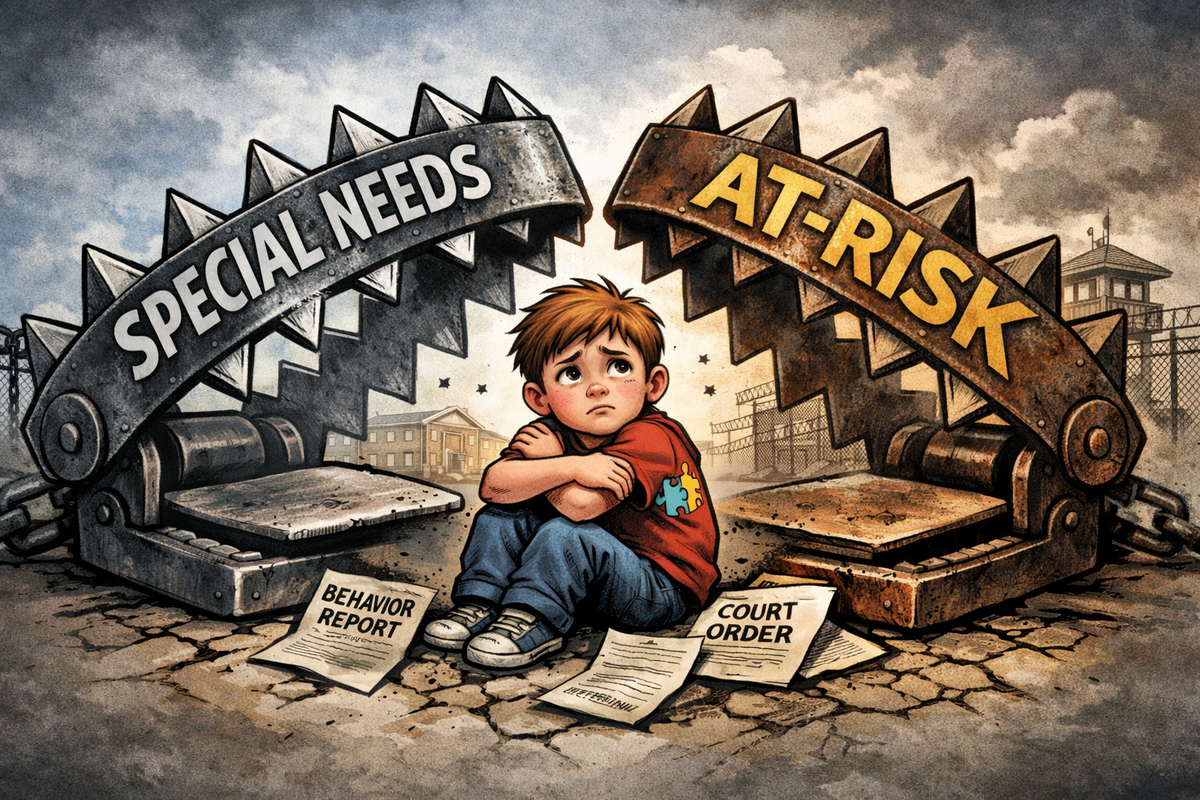

Increasingly, the answer may include children with disabilities, developmental differences, trauma histories, or neurological conditions — not because those children are more dangerous, but because they are statistically more likely to display behaviors that fall into broad behavioral risk categories.

This is not speculation. It is a well-documented reality across education, mental health, and juvenile justice research: impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, literal thinking, delayed executive function, and crisis language are common characteristics across multiple disability diagnoses. In educational environments, those behaviors are often addressed through accommodation plans, behavioral supports, or therapeutic intervention. In legal frameworks built around risk classification, those same behaviors can be interpreted through a different lens — one focused on threat assessment, supervision need, or public safety concern.

Tennessee’s existing juvenile detention law, Tennessee Code § 37-1-114, was historically structured to prevent premature detention by requiring probable cause tied to specific acts or immediate safety threats. The statute explicitly requires that detention occur only when no less restrictive alternative exists — creating a high threshold before the state removes a child from parental custody or places them in secure confinement.

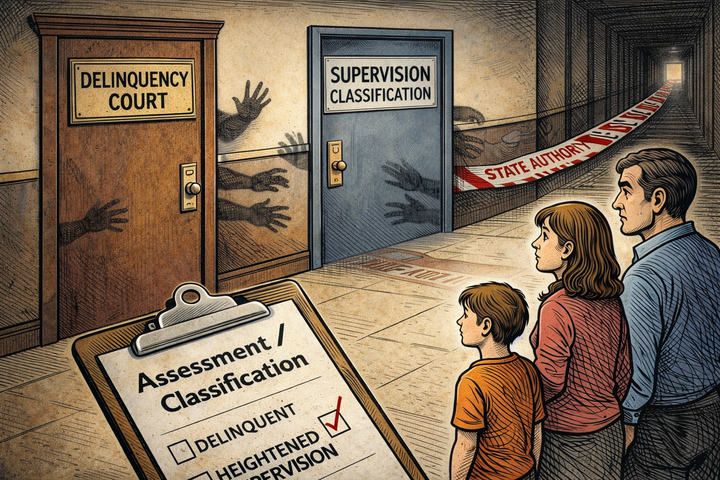

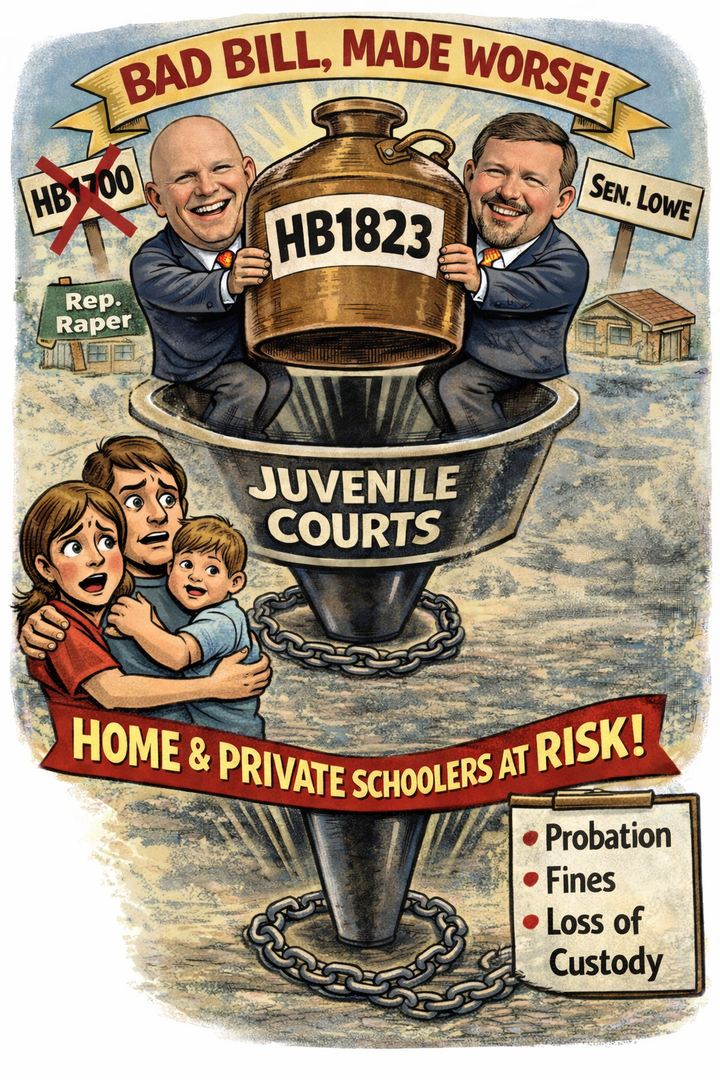

Recent legislative proposals such as SB1868, however, introduce additional classification pathways — including “child in need of heightened supervision” — that may apply based on behavior patterns consistent with violent conduct or threat expression, even absent formal delinquency adjudication.

The policy rationale behind such classifications is straightforward: intervene earlier when warning signs appear. But the structural question is more complex: how precisely are those warning signs defined, and how reliably can they be distinguished from disability-driven behavioral expression?

Because for many families raising children with autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, reactive attachment disorder, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, or severe trauma-related emotional disturbance, behaviors that can appear threatening in isolation are often part of disability-related crisis response rather than criminal intent.

Consider crisis language. Many disability specialists note that children experiencing emotional overload may use extreme or dramatic language without comprehension of legal implications or real-world feasibility. In education settings, this typically triggers behavioral intervention review. In a law enforcement context, the same language can trigger threat-based legal response.

This becomes particularly relevant in Tennessee, where “threat of mass violence on school property” (TCA § 39-11-106) is already listed among detention-triggering offenses under existing statute. The law itself was written to address legitimate safety concerns. But when paired with expanded classification systems that allow earlier intervention based on perceived risk rather than completed action, the interpretation environment changes.

Credit: Williamson County Schools YouTube

The problem is compounded by the fact that TCA § 39-11-106 focuses more on defining what a “threat” is than proving someone actually has means and intention to carry it out. This is what in criminal law is called an intent element. Which many legal experts would agree, is essential to substantiate constitutionality in a criminal statute. This can allow decisions to be based on how words are interpreted instead of real intent or real ability to do harm. When words alone can be treated as proof of danger, it creates a lot of room for subjective judgment and possible violations of due process.

And it is at that intersection — disability behavior versus threat classification — where the vulnerability gap may emerge.

None of this means expanded supervision statutes automatically will result in disproportionate detention of special needs children. But it does raise serious questions about screening safeguards. Specifically: should disability evaluation be required before behavioral classification triggers deeper state supervision pathways?

Federal law already recognizes this risk. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires behavioral manifestation review when discipline involves students with disabilities. The principle is simple: behavior must be evaluated in context of disability before punishment or removal occurs.

It defies basic policy logic to allow the state to label or escalate control over a child before determining whether disability is driving the behavior. Safeguards only work if they exist at the front end, not after harm is already done.

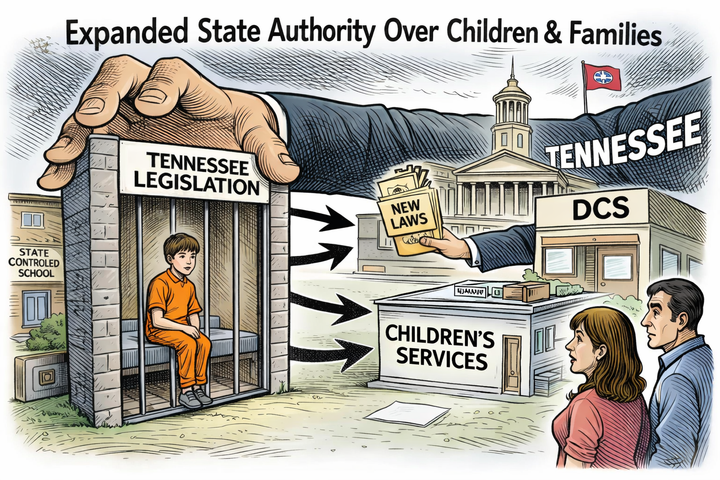

At the same time, classification expansion is occurring alongside broader “at-risk youth” policy structures, including educational placement models such as Opportunity Public Charter Schools (SB2820 / HB2922), which define eligibility based on overlapping behavioral, academic, and socioeconomic risk indicators.

Again, the policy goal is intervention and support. But when multiple classification systems overlap — juvenile supervision classification, education risk classification, and child welfare risk assessment — the cumulative effect can increase system visibility for children already navigating complex developmental or mental health challenges.

And this is where the broader philosophical question emerges — especially in a state that publicly emphasizes parental rights and limited government intervention.

If Tennessee’s policy identity is grounded in family autonomy and parent-led decision-making, then classification expansion invites legitimate public questions:

Should behavioral risk categories include explicit disability screening safeguards?

Should classification-triggered supervision require independent evaluation before long-term state oversight begins?

Should statutes explicitly differentiate between criminal threat behavior and disability-related crisis behavior?

These are not accusations about legislative motive. They are policy design questions about system architecture.

Because classification frameworks do not exist in theory. They exist in implementation — inside schools, inside courtrooms, inside intake offices, inside child welfare systems.

And implementation outcomes are shaped by how precisely law defines thresholds.

For families raising special needs children, those thresholds are not abstract. They are lived reality.

Every classification expansion changes the margin of interpretation.

Every new behavioral category expands who can be evaluated for supervision need.

Every lowered threshold increases the number of entry points into systems that can be extremely difficult for families to navigate once entered.

For some children, early intervention may prevent crisis escalation. For others, early classification may introduce system involvement before therapeutic or family-based interventions are fully explored.

And that tension — protection versus overreach — is not unique to Tennessee. It exists in every state attempting to balance public safety with family autonomy.

But it becomes particularly relevant in states that publicly position themselves as defenders of parental authority.

Because when policy direction and political identity diverge, public trust questions follow naturally.

If the state emphasizes parental rights, families may reasonably ask how new classification frameworks reinforce — rather than bypass — parental authority.

If the state emphasizes limited government intervention, families may ask how early supervision classification aligns with that principle.

And if the state emphasizes child protection, families may ask how disability-specific safeguards are built into classification systems designed for early intervention.

Those questions do not assume bad intent. They assume responsible governance requires ongoing scrutiny — especially when policy changes affect the most vulnerable populations.

And increasingly, those populations include children whose behaviors are shaped not by criminal intent, but by neurological and developmental reality.

That brings the series to its next layer of examination — one that moves beyond classification systems and into the structural environment surrounding children once they enter state-supervised systems.

Because classification authority is only one part of the system architecture.

The next question is: who operates the systems children are placed into — and how those systems are structured, funded, and legally protected.

Coming Next in the Series

Article 5: The Contractor Ecosystem — Funding, Liability Shields, and the Expanding Infrastructure Surrounding Child Welfare Systems

Because once children enter state systems, the question shifts from who is classified to who benefits from the system that receives them.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()