Tennessee policy is expanding how “at-risk” youth are identified, classified, and placed. Article 3 examines how education, detention, and funding systems may intersect — and what that could mean for families and parental authority statewide.

(TruthWire Investigative Series — Part 3)

A TruthWire Investigation into Family Authority, State Power, and Tennessee Law

If public policy often moves in dramatic bursts, it more frequently moves in quiet increments — redefining words, expanding categories, and adjusting thresholds in ways that can fundamentally reshape how law interacts with families. Nowhere is that more evident than in the growing use of classification language such as “at-risk,” “unruly,” or “in need of supervision.”

At first glance, these terms appear protective. They signal intervention before tragedy, prevention instead of punishment, and early support instead of late crisis response. But classification language inside statutes carry weight far beyond its wording. It determines who can be detained, who can be removed from parental custody, and who can be placed into state-directed programs — sometimes before adjudication of wrongdoing ever occurs.

To understand the modern shift, it is important to begin with the baseline protections already embedded in Tennessee law.

Current Tennessee statute governing juvenile detention is codified under Tennessee Code § 37-1-114, which establishes strict thresholds for detaining a child prior to a hearing. The law requires probable cause tied to specific conditions, including delinquent acts, immediate safety threats, or serious flight risk — and requires that detention be used only when no less restrictive alternative exists.

Historically, this framework created a narrow gateway into detention or state custody. The standard required either an alleged delinquent act or a demonstrable, immediate safety threat. In practice, this meant state intervention generally followed an identifiable event.

But newer legislative proposals and amendments have begun introducing broader behavioral classifications — categories that do not always require a completed act, adjudication, or even formal delinquency proceedings before state intervention mechanisms activate.

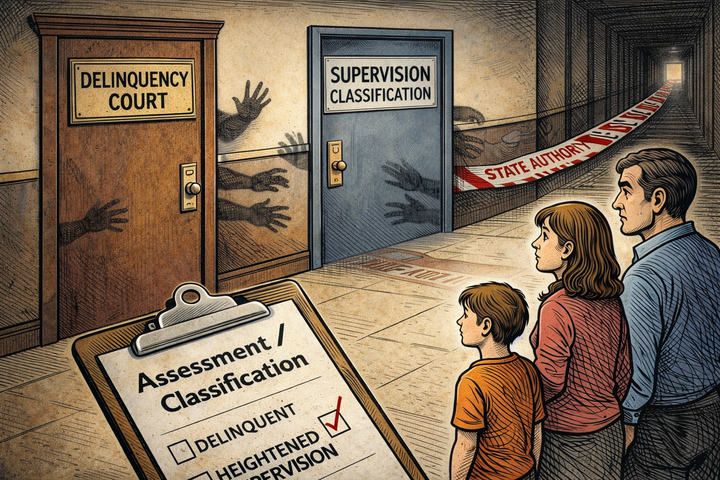

One example comes from proposals such as SB1868, which introduces the classification “child in need of heightened supervision.” The classification can be applied based on behavior consistent with violent conduct or threat-based behavior, even if no delinquency adjudication occurs.

While the bill language frames this as preventative safety policy, it raises structural questions about how far classification authority can expand before it begins reshaping due process expectations in juvenile proceedings.

At the same time, classification expansion is not occurring in isolation. It is happening alongside broader policy developments around “at-risk youth,” particularly within educational and residential placement policy.

For example, legislation related to Opportunity Public Charter Schools (SB2820 / HB2922, enacted 2024) created a framework for specialized schools serving populations defined by risk factors including:

• Prior juvenile system involvement

• Chronic absenteeism

• Academic retention history

• Substance abuse history

• Pregnancy or parenting status

• Exposure to abuse or neglect

• Household income thresholds

• Prior detention or pending adjudication

Supporters of these policies consistently frame them as targeted interventions for historically underserved youth. And in many cases, the stated goals are prevention-focused — improving educational outcomes, reducing recidivism, and stabilizing vulnerable youth populations.

But the structural question that naturally emerges is not about intent — it is about scope.

What happens when multiple policy layers expand classification authority simultaneously?

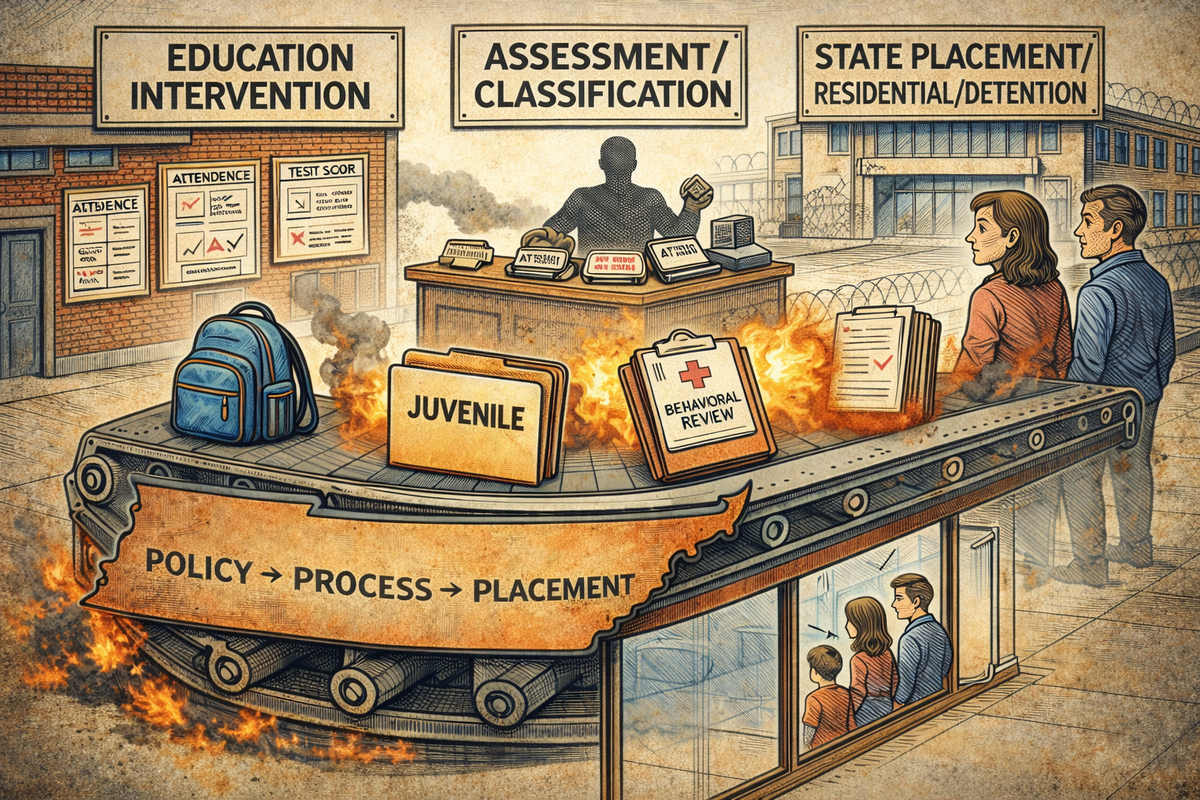

When behavioral classification expands in juvenile law…

When risk classification expands in education policy…

When detention authority expands in supervision statutes…

…the cumulative effect can create a much wider entry point into state-directed systems than any single law appears to create on its own.

This is where policy analysis shifts from bill-by-bill evaluation to system architecture analysis.

Because classification frameworks do not exist independently. They interact.

A child flagged under school-based “risk” classification can become visible to social services systems.

A behavioral threat classification can become relevant to juvenile intake decisions.

A supervision classification can become relevant to placement authority.

None of these mechanisms individually guarantee removal, detention, or state custody. But together, they can create overlapping jurisdictional pathways.

And it is at this intersection where public policy begins raising larger philosophical questions — especially in states that publicly emphasize parental rights and limited government intervention.

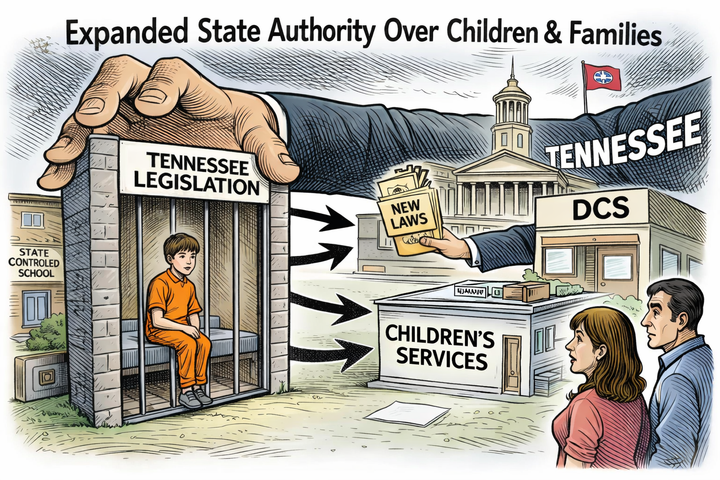

If Tennessee defines itself as a state prioritizing parental authority and family autonomy, then classification expansion invites natural public questions:

Where is the balance point between early intervention and premature state involvement?

How narrowly should risk categories be defined before they begin capturing children whose behavior reflects developmental, neurological, or disability-related factors rather than criminal or dangerous intent?

And how should due process protections evolve when intervention authority expands earlier in the behavioral timeline?

These questions become especially important when examining populations already statistically more likely to display behaviors associated with risk classification — including children with certain developmental disabilities, trauma histories, or behavioral regulation disorders.

Federal disability law, including IDEA protections, already recognizes that behavioral expression can be linked to underlying disability. The question for policymakers becomes whether classification-based statutes adequately incorporate that understanding — or whether disability screening must be explicitly embedded before classification triggers deeper system involvement.

These are not accusations. They are policy design questions.

And they are questions that emerge naturally when examining the cumulative direction of legislative change over multiple sessions rather than evaluating each bill in isolation.

Because public policy is rarely defined by a single bill.

It is defined by trajectory.

And across juvenile law, education policy, and risk classification frameworks, Tennessee’s trajectory appears to be moving toward earlier identification, earlier classification, and earlier intervention.

For some families, that trajectory represents protection and support.

For others, it raises deeper questions about how much authority the state should hold to classify children before wrongdoing is adjudicated — and how those classifications may shape the long-term relationship between families and state systems.

Those questions become even more significant when examining who operates the systems that receive children once they enter those pathways — and how those systems are structured, funded, and legally shielded.

That is where the series turns next.

Coming Next in the Series

Article 4: The Vulnerability Gap — Why Special Needs Children May Face Disproportionate Exposure to Risk-Based Classification Systems

Because the most important question may not be how classification systems are designed — but who is most likely to be captured by them.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()