HB1823 expands state power by routing students leaving public schools into juvenile court pipelines. Critics argue it discourages homeschool and private school options while increasing court authority over families and parental education decisions.

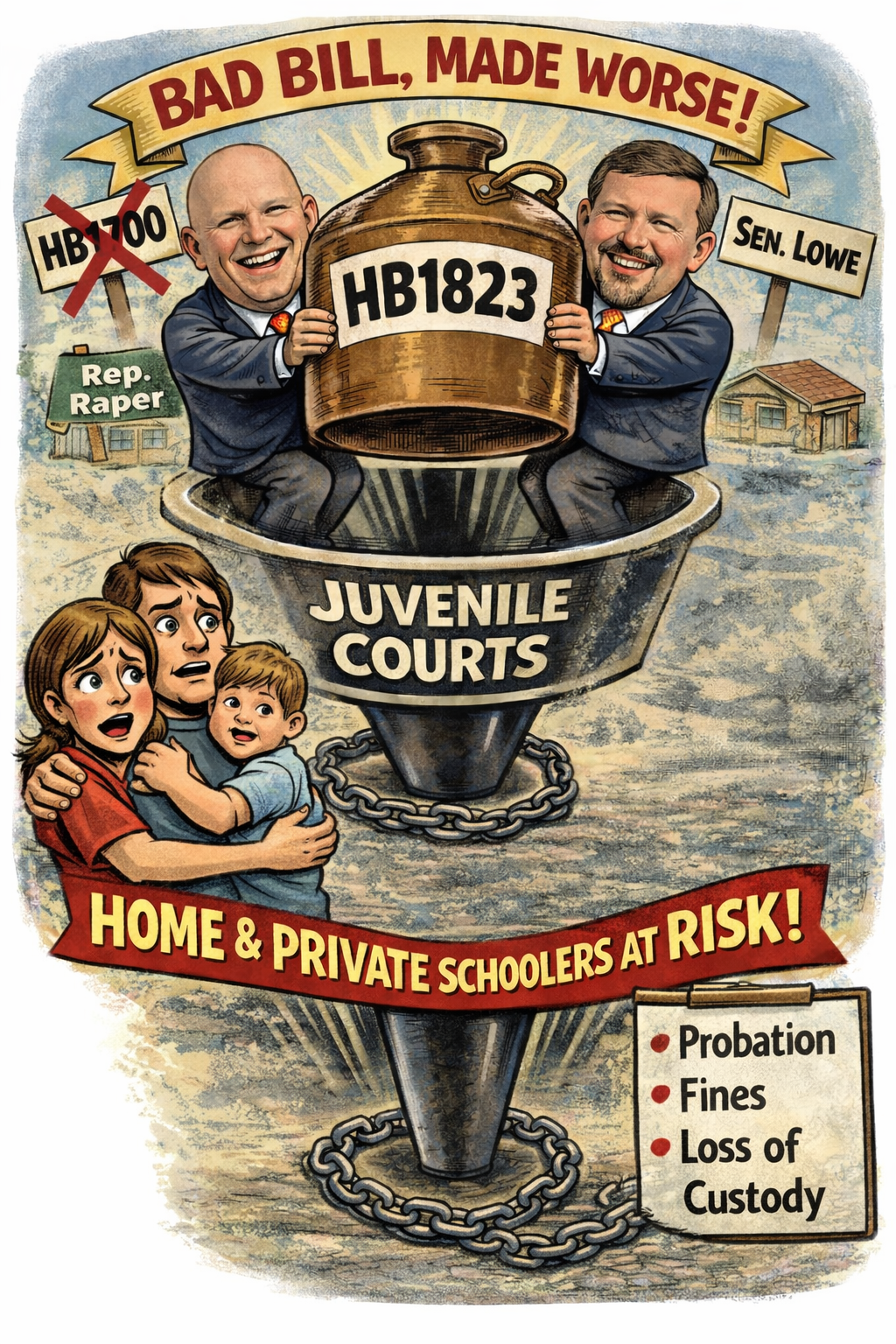

The history of HB1823 is just a little bit more complicated than first glance indicates- because HB1823 is very clearly derived from the recently withdrawn (before any consideration) HB1700. They share sponsors; they share language; they share a common date (HB1823 was filed the day HB1700 was withdrawn). In fact, HB1823 differs from HB1700 only by a few words and a new Section 4. Unfortunately, HB1700 was a bad bill, and HB1823 makes it worse.

HB1823 has five sections. Section 1 modifies Section 49-6-3001(c)(1)(B)(i), requiring that schools transfer attendance records along with students (all statutes cited are accessible through this portal). So far so good. Section 2 has a bunch in it; we’ll come back to that in a moment. Section 3 is subsidiary to the previous section. Section 4, new to HB1823, will also return later. Section 5 (Section 4 in HB1700) simply requires schools to include other school’s attendance records in their truancy tally. Section 6 caps it off with the formalities.

Section 2 of HB1700 was pretty straightforward. “If a student is enrolled in a home school… but was previously enrolled in an LEA and receiving tier two or tier three interventions…, then the director of schools shall report the student’s absences to the [juvenile court].” That judge would then, under §37-1-168, §37-1-132, and §37-1-131, assign governmental intervention service, probation, community service, or restitution- or, if he thought it mete, remove the parents’ custody of their kid.

Students transferring into home-school would presumably have very good attendance records (home-school parents tend to look ill upon student absences). The truancy interventions, meanwhile, are predicated upon the state’s interest in ensuring students attend school and get an education. Leaving aside whether that’s the state’s job, we see that the ostensible purpose of truancy interventions is fulfilled by home-schooling, removing the need for further state intervention. Yet this bill mandates an escalation of state involvement by turning the case over to the juvenile courts. The stakes too rise from attendance contracts and community service to probation and even loss of custody. For many, many families, this risk is not merely worrying but prohibitive; they’ll see no choice but to remain in public school, despite their desire to home-school, despite the fact home-schooling would answer to the state’s ostensible purposes. The state-run LEA, therefore, would keep the student (and the funding).

HB1823’s Section 2 is a little different, in a way at once insignificant and noticeable. Crucially, the modification is not a retreat from HB1700’s hostility to home-schooling. No, the modification is an expansion of that hostility. Rather than being sent specifically against homeschoolers, the director of schools is directed to report to the juvenile court any student who withdraws from a Tennessee LEA and “does not transfer to another LEA, as defined in § 49-1-103.” That definition limits ‘LEA’ to public schools, to be clear- so private schools, church schools, and homeschools are all excluded, as this government webpage makes clear. Apart from this expansion of scope from homeschool to all non-public schools, HB1823’s Section 2 is almost identical to HB1700’s (we’ll get to the second change in a minute).

Why would Rep. Raper and Sen. Lowe (and various co-sponsors) desire to involve the juvenile courts here? The trigger created by this legislation is the student’s transfer from public school to a non-public option. The obvious answer is that these congressmen see something wrong with non-public education. Other possible explanations take a similar tack: an interest in maintaining LEA funds by trapping students in them; a desire to keep students within government’s power to educate.

HB1700 and HB1823 do not just aim to reduce truancy. If the sponsors wished to transfer the truancy interventions from school to school, they could. A process could be built to change which school the guardian contracts to ensure the student attends. Community service barely needs an alteration, except in the paperwork. In-school intervention could be dealt with by the non-public schools in question, who will assuredly already have processes to deal with truancy. Homeschools, of course, would need essentially none of these and in principle should have none of them.

No, these bills, the withdrawn and the still active one both, commit the student who leaves public school into the tender arms of the juvenile courts. This measure should and will terrify plenty of families. They will hear this threat, and it will prevent them from taking steps- home-schooling or private school- which could not only solve the problem but improve the lives of their children, all because they don’t want to risk getting a bad judge, don’t want the stress and costs of a court case, don’t know precisely what risks they run, except that it could reach to loss of custody, a nightmare for every decent parent.

HB1823 is thus a furthering of the evil principles of HB1700. The update doesn’t withdraw any of the government over-reach. It chooses instead to spread that overreach out from homeschoolers to private schools and church schools, to any schools not run by the government. These institutions should recognize that HB1823 isn’t merely a foe of homeschoolers (which might drive business their way) but a dam to keep students in the public school system completely, without egress until their truancy interventions end. Hopefully, too, the various private schools decide to fight on principle and in wisdom by seeking to end the entire bill, rather than just amend away their students’ liability to it.

HB1823’s modifications, moreover, highlight an aspect of the bill which we should not ignore: the empowerment of the juvenile courts. Already the bill’s HB1700 version sought to put ex-truant homeschoolers into the juvenile court; HB1823’s second edit to Section 2 and its addition of Section 4 continue that trend. Raper and Lowe, apparently, wish to give the courts more and more ability to punish parents.

Sections 2 and 4 of HB1823 exhibit parallel divergence from HB1700- an edit to the text, in Section 2, and an addition of an entire section, in Section 4 (of HB1823). Under current law, if the LEA’s truancy intervention fails, the director of schools is directed to report the truant family to the juvenile court. In addition to the various sentences allowed by §37-1-132 (change in custody, probation, community service, restitution, etc), the judge is empowered to punish the parent with “a fine of up to fifty dollars ($50.00) or five (5) hours of community service, in the discretion of the judge” (§49-6-3009(g)). HB1700 had a similar provision for the homeschoolers subjected to it, in Section 2.

HB1823 omits “five (5) hours of” from its Section 2 and proposes, in its Section 4, to remove “five (5) hours of” from the current statute (§49-6-3009(g)). Now, this could be seen as allowing judges to apply sub-five-hour sentences (though I’m not sure the statutory construction supports that; it depends on whether ‘up to’ applied to the community service as well as the fine). If that was the purpose, however, the sensical course would not be this omission and deletion. The sensical course would be to add ‘up to’ prior to ‘five (5) hours.’ The better explanation for HB1823’s language is that this is exactly what it appears to be: an uncapping, allowing judges to impose more punitive punishments on parents and guardians- specifically, here, on those who dare remove their children from public education, however good their reasons.

For we should not regard truancy as necessarily malicious. Truancy need not have an evil or neglectful reason. It could be the parents’ kindness to a child shattered by the death of a relative or friend. It could be parents trying to accommodate a child’s unrecognized neurological disorder- an autism, PANS/ PANDAS, or other affliction the school might not recognize. It could be parents not wanting to expose their children to the chemicals floating around the school. It might even be parents who cannot bring themselves to expose their children to the pernicious doctrines promoted by public school or to the foul (even dangerous) company. Or a parent whose worry about a predatory teacher has not yet been quite assuaged. Truancy can be benevolent or even virtuous- and this bill would menace these people even more harshly than before.

HB1700 and HB1823 form a trajectory that assures us of this legislation’s ill-intent (or of its framers’ culpable neglect, at the kindest). It comes, moreover, from the vice-chair of the House’s education committee, from a member of the Senate’s education committee. These positions poise its sponsors well to speed this bill to completion, particularly as it is a bill promoting government power, not combating it, making it amenable to the mood of our current Republican leadership.

Attempts such as this, seeking to corral students in public school, to empower the state against parents, and to increase state control over your children, must be met with unrelenting opposition. God gives children to their parents for the parents to raise- not to the state. Rep. Raper and Sen. Lowe are here mounting an assault upon that God-given responsibility and upon its attendant-component freedom. This bill will not affect the great mass of homeschoolers or private schools, it is true. But if we fight only when the final step is poised to stomp us, we’ll lose the battle before it has begun.

God bless.

If you want to support what we do, please consider donating a gift in order to sustain free, independent, and TRULY CONSERVATIVE media that is focused on Middle Tennessee and BEYOND!

Comments ()